The Elizabethan People/Chapter 6

CHAPTER VI

CELEBRATION OF THE CALENDAR

IN a description of manners and customs such as this, the writer's main difficulty after the material is at hand is that of selection and arrangement. An absolutely complete survey of the field, even if such a survey were possible, would in no way fulfil the purposes of the present volume, which, the author hopes, sufficiently describes the times without, on the other hand, presuming either to the tediousness or volubility which is the peculiar birthright of the technological dictionary. In treating, then, of the Elizabethan celebration of the calendar, a few of the most important feast days and their customs have been described in detail as typical; the remainder is left to the dictionary or to the imagination, according as one or the other is at hand.

Yet a word may be said to advantage concerning the omitted portion of the calendar. It is well for Americans to bear in mind that in this country to-day the days of the calendar are not nearly so familiar to the people at large as they are to Englishmen. New Year's Day, St. Valentine's Day, Easter, the Fourth of July, and a score of others would be known to every school child; yet many a person of education might pause over the location of Epiphany, or even Shrove-Tuesday, and how often would a book of names be called to the assistance when it is a question of St. George and the Dragon or St. Crispan; and few of us know that so much of our daily conversation at an afternoon tea is but a tribute to the influence of St. Swithin. All this is different in England. Yet the difference in this respect between our familiar associations and those of Englishmen is no greater than the difference between the association of Englishmen of to-day and the Englishmen of three centuries ago.

Shakespeare lived at a time when the Roman Catholic calendar had not gone altogether out of fashion, and scarcely at all out of memory. All its days were still remembered, and some that were the distinctive property of the Roman Church were still observed in Protestant England as of old. There were numberless others common to both churches, and yet others, associated wholly with the new, making altogether a total of which we have little conception.

The reader of the present volume will probably find its main value in the assistance it lends to the appreciation of Elizabethan literature. What such a reader should constantly bear in mind is the Elizabethan familiarity with all these proper names. The student of to-day who pauses over an enthusiastic passage in Henry V. to look up St. Crispan meets with a delay that, had it been possible three hundred years ago, would have caused Shakespeare to omit the allusion. Richard III., in swearing by St. Paul, is using the name of a very familiar saint and friend. The mention of Shrove-Tuesday meant to the Elizabethans far more than pancakes; and St. George's Day was to them like the Fourth of July. Elsewhere a similar change in the popular relation to superstition and folklore belief is called to the attention of the reader. In both cases we should remember constantly that many of these allusions that have passed completely out of our ready and every day memory were still fresh and vital to the common audience of Shakespeare.

The year was ushered in and ushered out by the same set of festivities, for the Yule-Tide celebration began long before Christmas and extended to Twelfth Day. Both this and New Year's Day, as falling within this period, are described below at the end of the chapter. Though several days of minor importance were connected with annual celebration early in the year, a sort of popular relaxation manifested itself after the Christmas sports which was, however, boisterously brought to an end by the merry-making of Shrove-Tuesday. Since the time of the Reformation Shrove-Tide was no longer of such importance as a time for shriving and general confession of sins. The Protestant Elizabethans seized upon the carnival element of the Roman Catholic celebration and made the period before Lent one of the jolliest of the year. Collop Monday followed Shrove-Sunday; and was so-called as being the period when the people reluctantly bade good-bye to slices of meat called in some parts of the country collops. The next day was Pancake Tuesday, commemorating an article of diet that has not yet passed out of fashion as distinctively associated with the observation of Shrove-Tuesday.

Thomas Tusser, a chorister of St. Paul's, later joined the court as musician to William Paget, first baron Paget. He farmed, wrote poetry, and in 1557 (expanded in 1570 and 1573), published Hundreth Good Pointes of Husbandrie. One of his stanzas concerning Shrove-Tide is worth quoting:—

"At Shroftide to shroving, go thresh the fat hen,

If blindfold can kill her, then give it thy men:

Maids, fritters, and pancakes, now see ye make,

Let slut have one pancake, for company sake."

Concerning one of the customs alluded to above, Mr. Hilman says: "The hen is hung at a fellow's back, who has also some horse-bells about him; the rest of the fellows are blinded, and have bows in their hands, with which they chase this fellow and his hen about some large covert or small enclosure. The fellow with the hen and bells shifting as well as he can, they follow the sound, and sometimes hit him and his hen; at other times, if he can get behind one of them, they thrash one another well favour'dly; but the jest is, the maids are to blind the fellows, which they do with their aprons, and the cunning baggages will endear their sweet-hearts with a peeping hole, whilst the others look out as sharp to hinder it. After this the hen is boiled with bacon, and store of pancakes and fritters are made. She that is noted for lying in bed long, or any other miscarriage, hath the first pancake presented to her, which most commonly falls to the dogs' share at last, for no one will own it their due."[1]

In the prologue to Hawkin's Apollo Shroving, printed in 1626, we find this quatrain:—

"All which we on this stage shall act or say,

Doth solemnise Apollo's shroving day;

Whilst thus we greet you with our words and pens,

Our shroving bodeth to none but hens."

An answer in All's Well That Ends Well is "as fit as a pancake for Shrove-Tuesday;" and in Pericles this article of food is termed a flap-jack. There are numerous allusions to the pancake diet in the Elizabethan dramas; and of the pancake-bell Taylor, the Water Poet, has the following to say: "Shrove-Tuesday, at whose entrance in the morning all the whole kingdom is unquiet, but by that time the clock strikes eleven, which (by the help of a knavish sexton) is commonly before nine, then there is a bell rung, cal'd pancake-bell, the sound whereof makes thousands of people distracted, and forgetful either of manners or humanity."[2]

By the time of Elizabeth the cock-fighting mentioned by Fitzstephen,[3] who wrote in the time of Henry II., was coupled with or supplanted by the less sportsmanlike amusement of cock-throwing.The practice is thus described by Strutt:

"In some places it was a common practice to put the cock in an earthen vessel made for the purpose, and to place him in such a position that his head and tail might be exposed to view; the vessel, with the bird in it, was then suspended across the street, about twelve or fourteen feet from the ground, to be thrown at by such as chose to make trial of their skill; two pence was paid for four throws, and he who broke the pot, and delivered the cock from his confinement, had him for a reward."

The evening of Shrove-Tuesday was given up to dramatic entertainments. This was the custom both in town and country; at the court, in the halls of noblemen, and in the public theatres.

Shrove-Tuesday was considered by the apprentices as their particular holiday; and in the days of Shakespeare they considered it as their especial right to punish women of ill-fame, and to riot among the bawdy houses. Dekker, in The Seven Deadly Sins of London, says: "They presently (like prentices upon Shrove-Tuesday) take the law into their own hands and do what they list." And Sir Thomas Overbury, speaking of a bawd, remarks: " Nothing daunts her so much as the approach of Shrove-Tuesday." Says Ralph in The Knight of the Burning Pestle:—

"Farewell, all you good boys in merry London!

Ne'er shall we more on Shrove-Tuesday meet.

And pluck down houses of iniquity."[4]

"Jerusalem was a stately thing, and so was Nineveh, and the city of Norwich, and Sodom and Gomorrah, with the rising of the prentices, and pulling down the bawdy houses there upon Shrove-Tuesday."[5] "Ille beat downe the doore;

and put him in mind of a Shrove-Tuesday, the fatal day for the doors to be broken open."[6]

The theatres were also subject to these apprentice attacks, a fact alluded to by Middleton in The Inner Temple Masque. (11. 170-175.)

"Stand forth, Shrove-Tuesday, one a' the silenc'st bricklayers:

'Tis in your charge to pull down bawdy-houses.

To set your tribe a-work, cause spoil in Shoreditch,

And make a dangerous leak there; deface Turnbull,

And tickle Cod-piece Row; ruin the Cockpit:

The poor players never thrived in't."

Shoreditch and Turnbull were noted haunts of courtesans in London; Cod-piece Row, a name probably manufactured for the occasion. The Cockpit theatre was burned by the apprentices on Shrove-Tuesday, 1616. Dyce, in a note to this passage, points out that in the word leak there is an allusion to a bawdy house by Madam Leak, and quotes the following from Dekker's Owl's Almanacs: "Shrove-Tuesday falls on that day on which the prentices plucked down the Cockpit and on which they did always use to rifle Madam Leak's house at the upper end of Shoreditch."

Easter-tide, or the week following Easter, was a period of such exuberant merry-making that the people popularly imagined that their own mood was shared by the heavenly bodies, and believed that the sun actually danced with joy on the day of the Resurrection. It was the common custom to go out early upon Easter morning to watch the sun rise; and it is not improbable that, if the observers looked persistently at the new-risen luminary without wincing, they were often rewarded with a sight of this phenomenon.

Another of the numerous customs connected with this feast was most frequently practised in the north. At Newcastle the Mayor, Aldermen, and many burgesses used regularly at Easter and Whitsuntide to visit the Forth, with the mace, the sword, and the cap of maintenance triumphantly borne before in procession.

The morris-dance, especially connected with the May-day celebration, was also occasionally an element in the Easter sports. The principal outdoor game, however, played upon this occasion was hand-ball. It was played in all parts of the kingdom by the youth of both sexes, and the distinctive prize at this season of the year was a tansy cake. When Mercutio asked Benvolio whether he did "not fall out with a tailor for wearing his new doublet before Easter," he referred to the popular custom of wearing new clothes upon that day. It was, in fact, as necessary to wear something new on Easter in that time as it is to-day. Dyer tells us that it is still the custom for young folks in East Yorkshire to go to the nearest market-town on Easter Eve, where they buy some new article of dress to wear on the morrow in order to prevent the rooks from soiling their clothes during the coming year; and he quotes from Poor Robin's Almanac:—

"At Easter let your clothes be new.

Or else be sure you will it rue."

Egg-Saturday concluded the period of egg eating before Lent, and Easter began the resumption of the use of this article of diet; hence eggs were a principal feature of the Easter celebration. Then as now it was the custom to colour the Pasche eggs, as they were called, from the passover. Such eggs were considered by the young people in the light of fairings and were highly esteemed. Egg-giving was so prevalent a custom that it gave rise to the popular proverb: "I'll warrant you for an egg at Easter."

May-day was one of the great periods of open-air festivities. So anxiously did people look forward to the day that, as Shakespeare says, they could not sleep.

"Pray, sir, be patient; 'tis as much impossible …

Unless we sweep 'em from the door with cannons …

To scatter 'em, as 'tis to make 'em sleep

On a May morning." (Henry VIII.)

The day was ushered in by going a-maying, a custom that is thus described in Stow's Survey of London: "In the month of May, namely, on May-day in the morning, every man, except impediment, would walk into the sweete meaddowes and green woods, there to rejoice their spirits, with the beauty and savour of sweet flowers, praysing God in their kind."

This sedate and simple enjoyment, however, was not sufficient for most people. Stubbes, in The Anatomy of Abuses, thus describes the more usual form of maying:

"Against May-day every parish, town, or village assemble themselves, both men, women, and children; and either all together, or dividing themselves into companies, they goe, some to the woods and groves, some to the hills and mountains, some to one place, some to another, where they spend all the night in pleasant pastimes, and in the morning they return bringing with them birche boughs and branches of trees to deck their assemblies withal. But their chiefest jewel they bring from thence is the maie-poale, which they bring home with great veneration, as thus—they have twentie or fortie yoake of oxen, every oxe having a sweete nosegaie of flowers tied to the tip of his horns, and these oxen draw home the maie-poale, stinking idol rather, which they covered all over with flowers and hearbes, bound round with strings from the top to the bottome, and sometimes it was painted with variable colours, having two or three hundred men, women, and children following it with great devotion. And thus equipped it was reared with handkerchiefs and flags streaming on the top, they straw the ground round about it, they bind green boughs about it, they set up summer halles, bowers, and arbours hard by it, and then fall they to banquetting and feasting, to leaping and dancing about it, as the heathen people did about their idols."

It was also a custom of the time to deck the doors and porches with green sycamore and hawthorn boughs brought in with the May-pole. The habit of painting the May-pole in spiral lines of different bright colours, mentioned above, is also alluded to in A Midsummer Night's Dream where Hermia calls Helena a painted May-pole.

But the sport par excellence connected with the May-day revels was the morris-dance. "About the commencement of the sixteenth century, or somewhat sooner, probably towards the middle of the fifteenth century, a very material addition was made to the celebration of the rites of Mayday, by the introduction of Robin Hood and some of his associates, This was done with a view towards the encouragement of archery, and the custom was continued even beyond the close of the reign of James I. It is true that the May-games in their rudest form, the mere dance of lads and lasses round a May-pole, or the simple morris with the Lady of the May, were occasionally seen during the reign of Elizabeth; but the general exhibition was the more complicated ceremony we are about to describe."[7] To these characters were soon added several others, till, at its highest development under Elizabeth and James, the dramatis personæ of the morris-dance included the following characters: Robin Hood, Maid Marian, Friar Tuck, Little John, the Fool, Tom the Piper, the Hobby-Horse, the Dragon, and from two to ten morris-dancers, or the same number of Robin Hood's men, with the painted Maypole in the centre.

Robin Hood was created King or Lord of the May, and sometimes bore in his hand a painted standard. His paramour. Maid Marian, supplanted the former Queen of the May. Her part, in the days of Shakespeare, was usually taken by a smooth-faced lad whose unbroken voice rendered him capable of taking the part of a woman effectively. This custom gave offence to the Puritans, one of whom wrote in the following words:

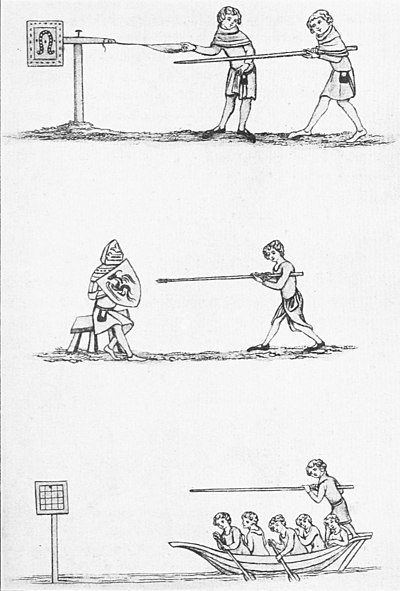

The Quintain.

(From Strutt's "Sports and Pastimes.")

"The abuses which are committed in your May-games are infinite. The first whereof is this, that you do use to attyre in woman's apparrell whom you doe most commonly call may-marrions, whereby you infringe that straight commandment given in Deut. xxii. 5, that men must not put on women's apparrell for fear of enormities. Nay, I myself have seene in a May-game a troupe, the greater part whereof hath been men, and yet have they been attyred so like unto women, that their faces being hidde (as they were indeede) a man could not discerne them from women. The second abuse, which of all others is the greatest, is this, that it hath been toulde that your morice dauncers have danced naked in nets: what greater enticement unto naughtiness could have been devised? The third abuse is that you (because you will loose no time) do use commonly to run into woods in the night time, amongst maidens, to fet bowes, in so much as I have hearde of tenne maidens which went to fet May, and nine of them came home with child."[8]

Friar Tuck was Robin Hood's chaplain. The Fool, Tom the Piper, and the dancers were mainly distinguished by their dress. Of the Hobby-horse and the Dragon, Drake speaks as follows: "The former was the resemblance of the head and tail of a horse, manufactured in paste-board, and attached to a person whose business it was, whilst he seemed to ride gracefully on its back, to imitate the prancings and curvettings of that noble animal, whose supposed feet were concealed by a foot-cloth reaching to the ground; and the latter, constructed of the same materials, was made to hiss and vibrate his wings, and was frequently attacked by the man on the hobby-horse, who then personated the character of St. George."[9]

The skilful management of the hobby-horse was a matter of great difficulty, and required considerable preliminary practice. A character who takes this part in Sampson's Vow Breaker is angry with his rival the mayor. The former calls out: "Let the mayor play the hobby-horse among his brethren, an he will. I hope our town lads cannot want a hobby-horse. Have I practiced my reines, my careers, my pranckers, my ambles, my false trotts, my smooth ambles and Canterbury paces, and shall master mayor put me besides the hobby-horse? Have I borrowed the fore horse bells, his plumes and braveries, nay, had his mane new shorne and frizzled, and shall the mayor put me besides the hobby-horse?" So important was the hobby-horse considered that the proverbial expression "The hobby-horse is forgot" was equivalent to our Hamlet with Hamlet left out."

The music of the morris-dance was furnished either by the simple pipe, the pipe and tabor, or the bagpipe. That the latter instrument was rather preferred is implied in the words announcing the arrival of Autolycus. "If you did but hear the pedlar at the door, you would never dance again after a tabor and pipe; no, the bagpipe could not move you." One of Thomas Weilkes' Madrigals, printed in 1600, has the following:—

"Harke, harke, I hear the dancing

And a nimble morris prancing;

The bagpipe and the morris bells,

That they are not farre hence us tells;

Come let us all go thither,

And dance like friends together."

The garments of the morris-dancers were adorned with bells which were meant to be wrung while dancing. They were fastened to the wrists, the elbows, and the ankles. They were of different sizes and tones and bore such names as the forebell, the second bell, the treble, the tenor or great bell, and double bells. The principal dancer was always superbly dressed. "He wants no clothes, for he hath a cloak laid on with gold lace, and an embroidered jerkin; and thus he is marching thither like the forman of a morris."[10]

Again, in Act iv. of The Knight of the Burning Pestle: "Let Ralph come out on May-day in the morning, and speak upon a conduit, with all his scarfs about him, and his feathers, and his rings, and his knacks;" and Ralph says in his declamation:—

"And by the common council of my fellows in the Strand,

With gilded staff and crossed scarf, the May-lord here I stand.

*****

The morris rings, while hobby-horse doth foot it faeteously:

The lords and ladies now abroad, for their disport and play,

Do kiss sometimes upon the grass and sometimes in the hay;

*****

And lift aloft your velvet heads, and slipping off your gown,

With bells on legs, and napkins clean unto your shoulders tied,

With scarfs and garters as you please, and 'Hey for our town!' cried.

*****

Up, then, I say, both young and old, both men and maid a-maying,

With drums and guns that bounce aloud and merry tabor playing."

The most complete and accurate description of the ancient morris-dance, though written in later times, is from the pen of the antiquarian Strutt, It is quoted here entire from his romance Queenhoo-Hall, vol. I, p. 13, etc.

"In front of the pavilion a large square was staked out, and fenced with ropes, to prevent the crowd from pressing upon the performers, and interrupting the diversion; there were also two bars at the bottom of the enclosure, through which the actors might pass and repass, as occasion required.

"Six young men first entered the square, clothed in jerkins of leather, with axes upon their shoulders like woodmen, and their heads bound with large garlands of ivy leaves intertwined with sprigs of hawthorn. Then followed,

"Six young maidens of the village, dressed in blue kirtles, with garlands of primroses on their heads, leading a fine sleek cow, decorated with ribbons of various colours, interspersed with flowers; and the horns of the animal were tipped with gold. These were succeeded by

"Six foresters, equipped in green tunics, with hoods and hosen of the same colour; each of them carried a bugle-horn attached to a baldric of silk, which he sounded as he passed the barrier. After them came

"Peter Laneret, the baron's chief falconer, who personified Robin Hood; he was attired in a bright grass-green tunic, fringed with gold; and his hood and his hosen were parti-coloured, blue and white; he had a large garland of rose-buds on his head, a bow bent in his hand, a sheaf of arrows at his girdle, and a bugle-horn depending from a baldric of light blue tarantine, embroidered with silver; he had also a sword and a dagger, the hilts of both being richly embossed with gold.

"Fabian, a page, as Little John, walked at his right hand; and Cecil Cellerman, the butler, as Will Stukely, at his left. These, with ten others of the jolly outlaw's attendants who followed, were habited in green garments, bearing their bows bent in their hands, and their arrows in their girdles. Then came

"Two maidens, in orange coloured kirtles with white courtpies (a short vest); strewing flowers; followed immediately by

"The Maid Marian, elegantly habited in a watchet-coloured tunic reaching to the ground; over which she wore a white linen rochet with loose sleeves, fringed with silver, and very neatly plaited; her girdle was of silver baudekin, fastened with a double bow on the left side; her long flaxen hair was divided into many ringlets, and flowed upon her shoulders; the top part of her head was covered with a rude net-work cawl of gold, upon which was placed a garland of silver, ornamented with blue violets. She was supported by

"Two brides-maidens, in sky-coloured rochets girt with crimson girdles, wearing garlands upon their heads of blue and white violets. After them came

"Four other females in green courtpies, and garlands of violets and cowslips. Then

"Sampson the smith, as Friar Tuck, carrying a huge quarter-staff upon his shoulder; and Morris the mole-taker, who represented Much the miller's son, having a long pole with an inflated bladder attached to one end.[11] And after them

"The May-pole, drawn by eight fine oxen, decorated with scarfs, ribbons, and flowers of divers colours; and the tips of their horns were embellished with gold. The rear was closed by

"The Hobby-horse and the Dragon.

"When the May-pole was drawn into the square, the foresters sounded their horns, and the populace expressed their pleasure by shouting incessantly until it reached the place assigned for its elevation: … and during the time the ground was preparing for its reception, the barriers of the bottom of the enclosure were opened for the villagers to approach, and adorn it with ribbons, garlands, and flowers, as their inclination prompted them.

"The pole being sufficiently onerated with finery, the square was cleared from such as had no part to perform in the pageant; and then it was elevated amidst the reiterated acclamations of the spectators. The woodmen and the milkmaidens danced around it according to the rustic fashion; the measure was played by Peretto Cheveritte, the baron's chief ministrel, on the bagpipes accompanied with the pipe and tabour, performed by one of his associates. When the dance was finished, Gregory the jester, who undertook to play the Hobby-horse, came forward with his appropriate equipment, and, frisking up and down the square without restriction, imitated the galloping, curvetting, ambling, trotting, and other paces of the horse, to the infinite satisfaction of the lower classes of the spectators. He was followed by Peter Parker, the baron's ranger, who personated a dragon, hissing, yelling, and shaking his wings with wonderful ingenuity; and to complete the mirth, Morris, in the character of Much, having small bells attached to his kneees and elbows, capered here and there between the two monsters in the form of a dance; and as often as he came near to the sides of the enclosure, he cast slyly a handful of meal into the faces of the gaping rustics, or rapped them about the heads with the bladder tied to the end of his pole. In the meantime, Sampson, representing Friar Tuck, walked with much gravity around the square, and occasionally let fall his heavy staff upon the toes of such of the crowd as he thought were approaching more forward than they ought to do; and if the sufferers cried out from the sense of pain, he addressed them in a solemn tone of voice, advising them to count their beads, say a paternoster or two, and to beware of purgatory. These vagaries were highly palatable to the populace, who announced their delight by repeated plaudits and loud bursts of laughter; for this reason they were continued for a considerable length of time; but Gregory, beginning at last to faulter in his paces, ordered the dragon to fall back; the well-nurtured beast, being out of breath, readily obeyed, and their two companions followed their example; which concluded this part of the pastime.

"Then the archers set up a target at the lower end of the Green, and made trial of their skill in a regular succession. ... Robin was therefore adjudged the conquerer; and the prize of honour, a garland of laurel embellished with variegated ribbons, was put upon his head; and to Stukely was given a garland of ivy, because he was the second best performer in that contest.

"The pageant was finished with the archery; and the procession began to move away, to make room for the villagers, who afterwards assembled in the square, and amused themselves by dancing round the May-pole in promiscuous companies, according to the ancient custom."

Of all the year no period was looked forward to with an interest like that inspired by the approach of Christmas and the following days. The principal characteristic of the Yule-tide sports was general hospitality and the closely related unbinding of social ties. It was the one time of the year when there was practically no distinction of class, when lord, lady, and rustic met in the same hall, played the same games, and romped without stint as if they were social equals. The proper period for the Yule-tide sports was from Christmas Eve to Twelfth Day; but, especially among the lower classes, this period was extended in both directions. It was customary during this period to decorate the halls, houses, etc., with bay, laurel, ivy, and holly leaves, decorations which were kept in place to the end of the period of celebration. An allusion in Stow's Survey of London to this habit contains also an allusion to the extension of the period of celebration by the common people. "Against the feast of Christmas," he says, "every man's house, as also their parish churches, were decked with holm, ivy, bays, and whatsoever the season of the year afforded to be green. The conduits and the standards in the streets were likewise garnished. Amongst which I read, that in the year 1444, by tempest of thunder and lightning, on the first of February at night, Paul's steeple was fired, but with great labour quenched, and towards the morning of Candlemas day, at the Leadenhall in Cornhill, a standard of tree, being set up in the pavement fast in the ground, nailed full of holm and ivy, for disport of Christmas to the people, etc."

On Christmas Eve the people were wont to light candles, called Christmas candles, of prodigious size, and to stir the fire till it burned with uncommon brightness. In the midst of this extra illumination the yule-log was brought in. It was the special duty of the household carpenter to provide the Christmas block which was the massive root or trunk of a tree capable of remaining a part of the fire for a number of days. It was brought into the centre of the hall on Christmas eve amid great rejoicing, and, while still there, each member of the household would come forward, seat himself or herself upon it and sing a Yule-song and drink to a merry Christmas and a happy New Year. It was then rolled amid a great tumult to the fire-place and, when properly set up and the material arranged about it for fire, the yule-log was actually ignited by the brand that had been expressively saved for the purpose from last year's Christmas fire. The whole household, including family, friends, and domestics then feasted to a late hour upon Yule-dough, Yule-cakes, and bowls of frumity, with much music and singing.

In Roman Catholic times special arrangements were made whereby the poorer people found it easy to collect money by begging, which was to be applied to the purchase of masses for the forgiveness of the excesses to which they went during the Christmas revels. In the time of Shakespeare this custom was still in vogue in the form of carols sung early on Christmas morning especially, as a regular custom, but also carols or songs of a more secular nature that were sung at all times during Yule-tide, with a collection to follow. This custom was frequently followed or accompanied by mumming where a number of persons went about together, from hall to hall, hoping for entertainment and gratuitous remuneration.

The dinner upon Christmas day was served with especial sumptuousness, with great attention paid to the "dishes for show," as Markham calls them, namely, fancy dishes representing objects, got up with great elaboration, but not meant to be eaten. Not exactly conforming to the latter requirement, however, was the peacock pie, in which the cock was cooked whole, with the head projecting through the crust. The head of the cock would be beautifully decorated at the serving, and the bill gilded; and the tail set up in all its extended grandeur of coloured beauty. Though the following description of a Christmas dinner is from Nichols's accounts of the court, it is not more elaborate than that of many of the noblemen of the court, and differs but little from the celebration of even less wealthy people:

"On Christmas day, service in the church being ended, the gentlemen presently repair into the hall to breakfast, with brawn, mustard, and malmsey.

"At dinner, the butler appointed for the Christmas is to see the tables covered and furnished: and the ordinary butlers of the house are decently to set bread, napkins, and trenchers, in good form, at every table; with spoons and knives. At the first course is served a fair and large boar's head, on a silver platter, with minstralsye.

"Two 'servants' are to attend at supper, and to bear two fair torches of wax, next before the musicians and trumpeters, and stand above the fire with the music, till the first course be served in through the hall. Which performed, they, with the music, are to return to the buttery. The like course is to be observed in all things during the time of Christmas.

"At night, after supper, are revels and dancing, during the twelve days of Christmas. The Master of the Revels is, after dinner and supper, to sing a caroll or song; and command other gentlemen then there present to sing with him and the company; and so it is very decently performed."

In Middleton's Father Hubbard's Tales a number of distinctively Christmas sports are alluded to, among which are carols, wassail bowls, the dancing of Sellinger's Round, Shoeing the Mare, Hoodman Blind, Hot-Cockles, and playing the King and Queen at Twelfth Night. Sellinger's Round, or The Beginning of the World as it was also called, is alluded to in Heywood's The Fair Maid of the West. "I am so tired with dancing with these same black shee chimney sweepers, that I can scarce set the best leg forward, they have so tir'd me with their mariscoes, and I have so tickled them with our country dances. Sellinger's Round, and Tom Tiler: we have so fiddled it."

Hoodman Blind is our Blind Man's Buff, and Hot-Cockles is a game still played under various names. One player was blind-folded and the others struck him, he trying to guess who had dealt the blow. Shoe the Mare was another boisterous Christmas sport. "One of the players was chosen to be the wild mare, and the others chased him about the room with the object of shoeing him." (Bullen.)

The Lord of Misrule or Abbot of Unreason is familiar to all readers of Sir Walter Scott. Of this personage, who figured, but with less importance, in the rites of Whitsuntide, was one of the most important officers of the Christmas celebration. "In the feast of Christmas," says Stow, "there was in the King's house wheresoever he lodged, a Lord of Misrule, or Master of merry desports, and the like had ye in the house of every nobleman of honour, or good worship, were he spiritual or temporal. Amongst the which, the Mayor of London and either of the Sheriffs had their several Lords of Misrule, ever contending without quarrel or offence, who should make the rarest pastimes to delight the beholders. These lords, beginning their rule on Alhallow Eve, continue the same till the morrow after the feast of the Purification, commonly called Candlemas Day. In which space there was fine and subtle disguisings, masques and mummeries, with playing at cards for counters, nayles and points, in every house, more for pastime than for gain." And Stubbes, in The Anatomy of Abuses, prints the following tirade:

"First, all the wilde heads of the parish, flocking together, chuse them a graunde captain (of mischief) whom they inrolle with the title of my Lord of misrule, and him they crown with great solemnities, and adopt for their king. This king annoynted, chooseth forth twentie, fourtie, three-score, or a hundred lustie guttes like to himselfe to wait upon his lordly majesty, and to guarde his noble person. . . . Thus all things set in order, then have they their hobby-horses, their dragons and other antiques, together with their baudie pipers, and thundering drummers, to strike up the Devils Daunce withall: then march this heathen company towards the church and churchyarde, their pypers pypyng, their drummers thundering, their stumps dauncing, their bells jyngling, their handkerchiefs fluttering about their heads like madmen, their hobby-horses and other monsters skirmishing amongst the throng: and in this sorte they goe to the church like devils incarnate, with such a confused noise, that no man can heare his own voyce. Then the foolish people they looke, they stare, they laugh, they fleere, and mount upon formes and pewes, to see these goodly pagants solemnised in this sort. Then, after this about the church they goe agine and agine, and so foorth into the church yard, where they have commonly their summer haules, their bowers and arbours, and banquetting houses set up, wherein they feast, banquet, and daunce all that day, and (peradventure) all that night too." This description, though it applies to the summer election of the Lord of Misrule, differs from the Christmas celebration only in the out-of-door element.

None was more familiar with the ancient customs of England and Scotland than Sir Walter Scott. The following from the introduction to the sixth canto of Marmion may well close this note on the celebration of the calendar:

"And well our Christian sires of old

Loved when the year its course had roll'd,

And brought blithe Christmas back again,

With all his hospitable train.

Domestic and religious rite

Gave honour to the holy night;

On Christmas-eve the bells were rung;

On Christmas-eve the mass was sung:

That only night in all the year,

Saw the stoled priest the chalice rear.

The damsel donn'd her kirtle sheen;

The hall was dress'd with holly green;

Forth to the wood did merry-men go,

To gather in the mistletoe.

Then open'd wide the Baron's hall

To vassal, tenant, serf, and all;

Power laid his rod of rule aside,

And Ceremony doff'd his pride.

The heir, with roses in his shoes,

That night might village partner choose;

The lord, underogating, share

The vulgar game of "post and pair."

All hail'd, with uncontroll'd delight,

And general voice, the happy night,

That to the cottage, as the crown,

Brought tidings of salvation down.

III

The fire, with well-dried logs supplied,

Went roaring up the chimney wide;

The huge hall-table's oaken face,

Scrubb'd till it shone, the day to grace,

Bore then upon its massive board

No mark to part the squire and lord.

Then was brought in the lusty brawn,

By old blue-coated serving-man;

Then the grim boar's head frown'd on high,

Crested with bays and rosemary.

Well can the green-garb'd ranger tell,

How, when, and where, the monster fell;

What dogs before his death he tore,

And all the baiting of the boar

The wassel round, in good brown bowls,

Garnish'd with ribbons, blithely trowls.

There the huge sirloin reek'd; hard by

Plum-porridge stood, and Christmas pie;

Nor fail'd old Scotland to produce,

At such high-tide, her savoury goose.

Then came the merry maskers in,

And carols roar'd with blithesome din?

If unmelodious was the song,

It was a hearty note, and strong.

Who lists may in their mumming see

Traces of ancient mystery;

White shirts supplied the masquerade,

And smutted cheeks the visors made;

But, O! what maskers, richly dight,

Can boast of bosoms half so light!

England was merry England, when

Old Christmas brought his sports again.

'Twas Christmas broach'd the mightiest ale;

'Twas Christmas told the merriest tale;

A Christmas gambol oft could cheer

The poor man's heart through half the year."

- ↑ Quoted by Drake, Vol. I, p. 143.

- ↑ Works, fol. 1630, p. 115.

- ↑ See chapter p.

- ↑ Act V., Scene iii.

- ↑ Jonson, Bartholomew Fair, Act V., Scene i.

- ↑ Dekker, Match me in London.

- ↑ Drake, Vol I., p. 159

- ↑ Featherstone's Dialogue agaynst light, lewde, and lascivious dancing, 1582. Quoted by Drake, Vol, I., p. 161.

- ↑ Vol, I., p. 166.

- ↑ The Blind Beggar of Bednal Green, Day,

- ↑ The mole-taker replaces the fool.