The Best Hundred Books/Criticisms and Lists by the Best Judges

CRITICISMS AND LISTS BY THE BEST JUDGES.

II—H.R.H. the Prince of Wales, Politicians, &c.

WE begin the criticisms on Sir John Lubbock's list with the letter of the Prince of Wales, whose interest in the advancement of letters is well known, and who courteously found time to answer our questions.

H.R.H. THE PRINCE OF WALES.

My dear Sir,—I am desired by the Prince of Wales to thank you for your letter of the 11th inst., and to assure you that he appreciates very sincerely the compliment which you are so good as to pay him in requesting him to draw up a catalogue of books which might seem to him to be the most conducive to a healthy mental state. The application is one which would require much time and thought to answer satisfactorily, and the Prince speaks, therefore, with diffidence when he expresses an opinion that the list suggested by Sir John Lubbock could hardly be improved upon. His Royal Highness would, however, venture to remark that the works of Dryden should not be omitted from such an important and comprehensive list.—I beg to remain, yours truly, Francis Knollys.

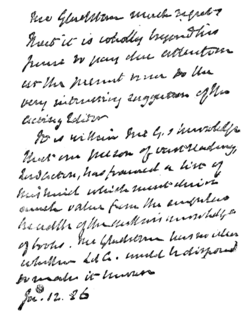

MR. GLADSTONE.

The late Prime Minister is like the Prince of Wales in at least one respect—both of them are men of encyclopædic interests. Mr. Gladstone is well known to be an omnivorous reader, and he was naturally among the first of the judges to whom we forwarded Sir John Lubbock's list. Mr. Gladstone replied by return of post, and on a post card, as follows:—

The general public were able to form some idea of Lord Acton's "vast reading" from his review of George Eliot's Life some months ago in the Nineteenth Century, and we hoped to have been able to lay before our readers the information to which Mr. Gladstone so properly attaches such high importance. Unfortunately, however, Lord Acton was abroad, and our letter did not reach him until after a considerable interval. He very kindly promised to write to us on the subject, but his letter has not reached us in time to be included in the present issue.

MR. CHAMBERLAIN.

Sir,—In reply to your inquiry I am directed by Mr. Chamberlain to say that he does not think he could greatly improve the list of books already submitted by Sir John Lubbock. He would, however, inquire whether it is by accident or design that the Bible has been omitted.—I am, yours obediently, Wm. Woodings.

PROFESSOR BRYCE, M.P.

The new Under-Secretary for Foreign Affairs has made himself so much of a political reputation in these latter years that we include him under the head of politicians. People are almost beginning to forget that he first made his reputation by a book ("The Holy Roman Empire"), and that he is still a University professor. Mr. Bryce wrote to us as follows:—

I am sorry to have been prevented by an accumulation of work from replying sooner to your request for a list of books "necessary for a liberal education," such as you have had from Sir John Lubbock. I have not time to furnish you with such a list, which would need a good deal of consideration, and would be quite different according as one assumes the person to be "liberally educated" to possess a wider or narrower knowledge of languages. There are books well deserving to be read in the original which are much less worth reading in translations.

However, I give you some additions to and criticisms on Sir John Lubbock's list which occur to me. I have not seen the remarks of your other correspondents, except Mr. Ruskin's. In Greek poetry Pindar ought to be substituted for Hesiod. In Greek philosophy Aristotle's Rhetoric and Poetic ought not to be omitted. Of Cicero it would be much better to have some Orations than the Offices or Old Age. St. Augustine's "De Civitate Dei" is indispensable. Perhaps no book ever more affected history. "The Icelandic Sagas," or some of them, ought to be added. Most of the best have been translated, such as "Njál's Saga," "Grettir's Saga," and the "Heimskringla." The poems in the "Elder Edda" (now admirably translated in Vigfusson and Powell's "Corpus Poeticum Boreale") ought also to find a place. For travels, add Marco Polo; for history, Machiavelli's "Prince." In Italian poetry Ariosto and Leopardi should come in. The "Lusiad" of Camoens is one of the finest examples of a poem in the grand style, and not the less interesting because the only work of Portuguese genius whose fame has overpassed the limits of its country. Montesquieu's "Esprit des Lois" is indispensable. So is "Candide." In modern fiction, "Les Misérables" and "The Scarlet Letter" may well replace Kingsley and Bulwer; the modern poets Keats and Shelley surely rank above Southey and Longfellow. Whether you put anything in its place or not (for example, Kant's "Kritik der reinen Vernunft," or Hegel's "History of Philosophy"), Lewes's "History of Philosophy" should be struck out,

THE LORD CHIEF JUSTICE OF ENGLAND.

Lord Coleridge wrote to us from the Judge's lodgings, Carmarthen, as follows:—

It is impossible for me at the time now at my disposal to attempt an answer to your very interesting letter. Indeed, if I had abundance of time, my reading has been so desultory and superficial, and since I left the University its course has been so much guided by wayward and passing fancies, that I should be sorry to suggest to any one else the books which happen to have delighted me.

Generally speaking, I think Sir John Lubbock's list a very good one as far as I know the books which compose it. But I know nothing of Chinese and Sanscrit, and have no opinion whatever about the Chinese and Sanscrit works he refers to. To the classics I should add Catullus, Propertiues, Ovid (in selections), Pindar, and the pastoral writers, Theocritus, Bion, and Moschus

I should find a place among epic poets for Tasso, Ariosto, and I should suppose Camoens, though I know him only in translation. With the poem of Malory on the "Morte d'Arthur," I am quite unacquainted; Malory's prose romance under that title is familiar to many readers from Southey's reprint of (I think) Caxton's edition of it.

Among the Greek dramatists, I should give a more prominent place to Euripides—the friend of Socrates, the idol of Menander, the admiration of Milton and Charles Fox; and I should exclude Aristophanes, whose splendid genius does not seem to me to atone for the baseness and vulgarity of his mind. In history I shall exclude Hume as mere waste of time now to read, and include Tacitus and Livy and Lord Clarendon and Sismondi. I do not know enough about philosophy to offer any opinion.

In poetry and general literature, I should certainly include Dryden and some plays of Ben Jonson and Ford and Massinger and Shirley and Webster; Gray, Collins, Coleridge, Chatles Lamb, De Quincey, Bolingbroke, Sterne, and I should substitute Bryant for Longfellow, and most certainly I should add Cowper.

In fiction I should add Miss Austen, "Clarissa," "Tom Jones," "Humphrey Clinker;" and certainly exclude Kings!ey. But I am well away from all books and with no time for reflection, and, though courtesy leads me to reply to a very courteous letter, I have no wish that a hasty and imperfect note such as this should be taken as representing a deliberate opinion.

HIS EXCELLENCY THE AMERICAN MINISTER.

Sir,—I cannot decline to reply to your courteous note touching "The Best Hundred Books," though it is a subject upon which I am by no means an authority, being only a casual wanderer in the field of letters. It seems to me not easy to lay out a course of reading that shall be of universal application. So much depends upon the cast of the reader's mind, his taste (if he has any), and the line of study he wishes to follow, that "the best laid scheme" may still "gang aft a-gley."

Sir John Lubbock's list already published is excellent, and perhaps cannot be improved. It is difficult to take from it, and, in trying to add, one encounters the embarrassment of riches. Taking that as a foundation were I to put my own inclination in the place of his better judgment, I should venture to increase it in general literature by the essays of Bacon, Johnson, Sterne, John Wilson, Carlyle, and Washington Irving, and the greater speeches of Webster. In poetry, by Chaucer, Dryden, Goldsmith, Gray, Coleridge, Burns, Byron, and Bryant. In fiction, by Cervantes and Le Sage, and all of Thackeray and Dickens that Sir John omits. In history, by Clarendon, Hallam, Macaulay, and the Americans Motley and Prescott. In political science, by Montesquieu's "Spirit of Laws," Guizot's "Civilization," and De Tocqueville's "Democracy." In the fine arts, by Lübke's "History of Art," Kugler's "Italian, Flemish, and Spanish Painters," Taylor's "Fine Art in Great Britain," and Fergusson's "History of Architecture."

If these additions carry the list beyond the limit, rather than lose my favourites, I would make room for them by cutting down somewhat the selections from translations of classical and Oriental literature, and from philosophy and theology, though retaining always in the latter John Bunyan and Jeremy Taylor. I cannot think the finis et fructus of liberal reading is reached by him who has not obtained in the best writings of our English tongue the generous acquaintance that ripens into affection. If he must stint himself, let him save elsewhere.

Even thus augmented, our list still excludes the whole range of living authors, all scientific, technical, and professional knowledge, and many charming books in literature, and enters but sparingly into the broad and fertile field of history. When these gaps are filled, the catalogue outruns us; and we find that as a book on one subject cannot be compared with that on another, no possible "hundred" can be exclusively "the best."

But after all power of choice has been exhausted, it still remains to be remembered that what good comes of it at last depends more upon digestion than upon acquisition. The reader who does not keep up a sound digestion will be apt to find good books disagree with him, and will only help to illustrate what is already sufficiently proved, that it is much easier to make a pedant, a prig, or a blatherskite than it is to make a scholar.—I am. Sir. your obedient servant,

III.—Men and Women of Letters.

NONE of our lists will, we imagine, be read with greater interest than those drawn up by men of letters. Everybody reads their books, and everybody will be interested to know what books they in their turn read. We ought here to explain that many of the judges whose verdicts are recorded later on might equally well have been included under this head; but we thought it would be more instructive, as well as more convenient, to allow ourselves the liberty of cross division.

MR. RUSKIN.

My dear Sir,—Putting my pen lightly through the needless—and blottesquely through the rubbish and poison of Sir John's list—I leave enough for life's liberal reading—and choice for any true worker's loyal reading. I should add one quite vital and essential book—Livy (the two first books), and three plays of Aristophanes (Clouds, Birds, and Plutus). Of travels I read myself all old ones I can get hold of; of modern, Humboldt is the central model. Forbes (James Forbes in Alps) is essential to the modern Swiss tourist—of sense.—Ever faithfully your,J. R.

The following is a facsimile of the list as "blottesquely" amended by Mr. Ruskin:—