Sophocles' King Oedipus

SOPHOCLES’

KING OEDIPUS

A VERSION FOR THE MODERN STAGE

BY

W. B. YEATS

“One does not expect to see an audience, drawn from all ranks of life, crowding a Theatre beyond its capacity and becoming awed into spellbound, breathless attention by a tragedy of Sophocles. Yet that is exactly what happened at the Abbey Theatre. . . . It was an event hitherto unequalled in the history of the Abbey, and when the chorus, standing before the closed curtain, spoke the concluding line, ‘Call no man happy while he lives,’ there followed a scene of enthusiasm surpassing all similar scenes with which the career of the Theatre is dotted. It was a spontaneous tribute such as almost beggared belief.”

MACMILLAN AND CO., LIMITED

ST. MARTIN’S STREET, LONDON

1928

SOPHOCLES’

KING OEDIPUS

MACMILLAN AND CO., Limited

LONDON · BOMBAY · CALCUTTA · MADRAS

MELBOURNE

THE MACMILLAN COMPANY

NEW YORK · BOSTON · CHICAGO

DALLAS · SAN FRANCISCO

THE MACMILLAN CO. OF CANADA, Ltd.

TORONTO

SOPHOCLES’

KING OEDIPUS

A VERSION FOR THE MODERN STAGE

BY

W. B. YEATS

MACMILLAN AND CO., LIMITED

ST. MARTIN’S STREET, LONDON

1928

COPYRIGHT

PRINTED IN GREAT BRITAIN

BY R. & R. CLARK, LIMITED, EDINBURGH

PREFACE

This version of Sophocles’ play was written for Dublin players, for Dublin liturgical singers, for a small auditorium, for a chorus that must stand stock still where the orchestra are accustomed to put their chairs, for an audience where nobody comes for self-improvement or for anything but emotion. In other words, I put readers and scholars out of my mind and wrote to be sung and spoken. The one thing that I kept in mind was that a word unfitted for living speech, out of its natural order, or unnecessary to our modern technique, would check emotion and tire attention.

Years ago I persuaded Florence Farr to so train the chorus for a Greek play that the sung words were almost as intelligible and dramatic as the spoken; and I have commended that art of hers in Speaking to the Psaltery. I asked my Dublin producer Lennox Robinson to disregard that essay, partly because liturgical singers were there to his hand, but mainly because if a chorus stands stock still in half shadow music and singing should, perhaps, possess a variety of rhythm and pitch incompatible with dramatic intelligible words. The main purpose of the chorus is to preserve the mood while it rests the mind by change of attention. A producer who has a space below the level of the stage, where a chorus can move about an altar, may do well to experiment with that old thought of mine and keep his singers as much in the range of the speaking voice as if they sang ‘The west’s awake’ or sang round a binnacle. However, he has his own singers to think of and must be content with what comes to hand.

- June 1st.

The Cast of First Production of King Oedipus, Abbey Theatre, Dublin, Tuesday, December 7, 1926.

| Oedipus | F. J. McCormick |

| Jocasta | Eileen Crowe |

| Creon | Barry Fitzgerald |

| Priest | Eric Gorman |

| Tiresias | Michael J. Dolan |

| Boy | D. Breen |

| First Messenger | Arthur Shields |

| Herdsman | Gabriel J. Fallon |

| Second Messenger | P. J. Carolan |

| Nurse | May Craig |

| Children | Raymond and Edna Fardy |

| Servants | Tony Quinn, Michael Scott, C. Haughton |

| Leader of the Chorus | J. Stevenson |

| Chorus | Peter Nolan, Walter Dillon, T. Moran, M. Finn, D. Williams |

Scene : Outside the Palace of King Oedipus

Produced by Lennox Robinson

KING OEDIPUS

Oedipus. Children, descendants of old Cadmus, why do you come before me, why do you carry the branches of suppliants, while the city smokes with incense and murmurs with prayer and lamentation? I would not learn from any mouth but yours, old man, therefore I question you myself. Do you know of anything that I can do and have not done? How can I, being the man I am, being King Oedipus, do other than all I know? I were indeed hard of heart did I not pity such suppliants.

Priest. Oedipus, King of my country, you can see our ages who are before your door; some it may be too young for such a journey, and some too old, Priests of Zeus such as I, and these chosen young men; while the rest of the people crowd the market-places with their suppliant branches, for the city stumbles towards death, hardly able to raise up its head. A blight has fallen upon the fruitful blossoms of the land, a blight upon flock and field and upon the bed of marriage—plague ravages the city. Oedipus, King, not god but foremost of living men, seeing that when you first came to this town of Thebes you freed us from that harsh singer, the riddling sphinx, we beseech you, all we suppliants, to find some help. Whether you find it by your power as a man, or because, being near the gods, a god has whispered you. Uplift our State; think upon your fame; your coming brought us luck, be lucky to us still, remember that it is better to rule over men than over a waste place, since neither walled town nor ship is anything if it be empty and no man within it.

Oedipus. My unhappy children! I know well what need has brought you, what suffering you endure, yet sufferers though you be, there is not a single one whose suffering is as mine—each mourns himself, but my soul mourns the city, myself, and you. It is not therefore as if you came to arouse a sleeping man. No! Be certain that I have wept many tears and searched hither and thither for some remedy. I have already done the only thing that came in to my head for all my search. I have sent the son of Menoeceus, Creon, my own wife’s brother, to the Pythian House of Phoebus, to hear if deed or word of mine may yet deliver this town. I am troubled, for he is a long time away—a longer time than should be—but when he comes I shall not be an honest man unless I do whatever the god commands.

Priest. You have spoken at the right time. They have just signalled to us that Creon has arrived.

Oedipus. O King Apollo, may he bring brighter fortune, for his face is shining.

Priest. He brings good news, for he is crowned with bay.

Oedipus. We shall know soon. Brother-in-law, Menoeceus’ son, what news from the god?

Creon. Good news; for pain turns to pleasure when we have set the crooked straight.

Oedipus. But what is the oracle—so far the news is neither good nor bad.

Creon. If you would hear it with all these about you, I am ready to speak. Or do we go within?

Oedipus. Speak before all. The sorrow I endure is less for my own life than these.

Creon. Then, with your leave, I speak. Our lord Phoebus bids us drive out a defiling thing that has been cherished in this land.

Oedipus. By what purification?

Creon. King Laius was our king before you came to pilot us.

Oedipus. I know—but not of my own knowledge, for I never saw him.

Creon. He was killed; and the god now bids us revenge it on his murderers, whoever they be.

Oedipus. Where shall we come upon their track after all these years? Did he meet his death in house or field, at home or in some foreign land?

Creon. In a foreign land: he was journeying to Delphi.

Oedipus. Did no fellow-traveller see the deed? Was there none there who could be questioned?

Creon. All perished but one man who fled in terror and could tell for certain but one thing of all he had seen.

Oedipus. One thing might be a clue to many things.

Creon. He said that they were fallen upon by a great troop of robbers.

Oedipus. What robbers would be so daring unless bribed from here?

Creon. Such things were indeed guessed at, but Laius once dead no avenger arose. We were amid our troubles.

Oedipus. But when royalty had fallen what troubles could have hindered search?

Creon. The riddling sphinx put those dark things out of our thoughts—we thought of what had come to our own doors.

Oedipus. But I will start afresh and make the dark things plain. In doing right by Laius I protect myself, for whoever slew Laius might turn a hand against me. Come, my children, rise up from the altar steps; lift up these suppliant boughs and let all the children of Cadmus be called hither that I may search out everything and find for all happiness or misery as god wills.

Priest. May Phoebus, sender of the oracle, come with it and be our saviour and deliverer.

(The Chorus enter.)

Chorus. What message comes to famous Thebes from the Golden House?

What message of disaster from that sweet-throated Zeus?

What foul things that our fathers saw, do the seasons bring?

Or what that no man ever saw, what new monstrous thing?

Trembling in every limb I raise my loud importunate cry,

And in a sacred terror wait the Delian god’s reply.

Apollo chase the god of death that leads no shouting men,

Bears no rattling shield and yet consumes this form with pain,

Famine takes what the plague spares, and all the crops are lost;

No new life fills the empty place—ghost flits after ghost

To that god-trodden western shore, as flit benighted birds.

Sorrow speaks to sorrow and finds no comfort in words.

Hurry him from the land of Thebes with a fair wind behind

Out on to that formless deep where not a man can find

Hold for an anchor fluke, for all is world-enfolding sea;

Master of the thundercloud, set the lightning free,

And add the thunder-stone to that and fling them on his head

For death is all the fashion now, till even death be dead.

We call against the pallid face of this god-hated god

The springing heel of Artemis in the hunting sandal shod,

The towsel-headed Maenads, blown torch and drunken sound,

The stately Lysian king himself with golden fillet crowned,

And in his hands the golden bow and the stretched golden string,

And Bacchus’ wine-ensanguined face that all the Maenads sing.

Oedipus. You are praying, and it may be that your prayer will be answered; that if you hear my words and do my bidding you may find help out of all your trouble. This is my proclamation, children of Cadmus. Whoever among you knows by what man Laius, son of Labdicus, was killed, must tell all he knows. If he fear for himself and being guilty denounce himself, he shall be in the less danger, suffering no worse thing than banishment. If on the other hand there be one that knows that a foreigner did the deed, let him speak, and I shall give him a reward and my thanks: but if any man keep silent from fear or to screen a friend, hear all what I will do to that man. No one in this land shall speak to him, nor offer sacrifice beside him; but he shall be driven from their homes as if he himself had done the deed. And in this I am the ally of the Pythian God and of the murdered man, and I pray that the murderer’s life may, should he be so hidden and screened, drop from him and perish away, whoever he may be, whether he did the deed with others or by himself alone: and on you I lay it to make—so far as man may—these words good, for my sake, and for the god’s sake, and for the sake of this land. And even if the god had not spurred us to it, it were a wrong to leave the guilt unpurged, when one so noble, and he your king, had perished; and all have sinned that could have searched it out and did not: and now since it is I who hold the power which he held once, and have his wife for wife—she who would have borne him heirs had he but lived—I take up this cause even as I would were it that of my own father. And if there be any who do not obey me in it, I pray that the gods send them neither harvest of the earth nor fruit of the womb; but let them be wasted by this plague, or by one more dreadful still. But may all be blessed for ever who hear my words and do my will.

Chorus. We do not know the murderer, and it were indeed more fitting that Phoebus, who laid the task upon us, should name the man.

Oedipus. No man can make the gods speak against their will.

Chorus. Then I will say what seems the next best thing.

Oedipus. If there is a third course, show it.

Chorus. I know that our lord, Tiresias, is the seer most like to our lord Phoebus, and through him we may unravel all.

Oedipus. So I was advised by Creon, and twice already have I sent to bring him.

Chorus. If we lack his help we have nothing but vague and ancient rumours.

Oedipus. What rumours are they? I would examine every story.

Chorus. Certain wayfarers were said to have killed the king.

Oedipus. I know. I know. But who was there that saw it?

Chorus. If there is such a man, and terror can move him, he will not keep silence when they have told him of your curses.

Oedipus. He that such a deed did not terrify will not be terrified because of a word.

Chorus. But there is one who shall convict him. For the blind prophet comes at last—in whom alone of all men the truth lives.

(Enter Tiresias, led by a boy.)

Oedipus. Tiresias, master of all knowledge, whatever may be spoken, whatever is unspeakable, whatever omens of earth and sky reveal, the plague is among us, and from that plague, Great Prophet, protect us and save us. Phoebus in answer to our question says that it will not leave us till we have found the murderers of Laius, and driven them into exile or put them to death. Do you therefore neglect neither the voice of birds, nor any other sort of wisdom, but rescue yourself, rescue the State, rescue me, rescue all that are defiled by the deed. For we are in your hands, and what greater task falls to a man than to help other men with all he knows and has.

Tiresias. Aye, and what worse task than to be wise and suffer for it. I know this well; it slipped out of mind, or I would never have come.

Oedipus. What now?

Tiresias. Let me go home. You will bear your burden to the end more easily, and I bear mine—if you but give me leave for that.

Oedipus. Your words are strange and unkind to the State that bred you.

Tiresias. I see that you, on your part, keep your lips tight shut, and therefore I have shut mine that I may come to no misfortune.

Oedipus. For god’s love do not turn away—if you have knowledge. We suppliants implore you on our knees.

Tiresias. You are fools—I will bring misfortune neither upon you nor upon myself.

Oedipus. What is this? You know all and will say nothing? You are minded to betray me and Thebes?

Tiresias. Why do you ask these things? You will not learn them from me.

Oedipus. What! Basest of the base! You would enrage the very stones. Will you never speak out? Cannot anything touch you?

Tiresias. The future will come of itself though I keep silent.

Oedipus. Then seeing that come it must, you had best speak out.

Tiresias. I will speak no further. Rage if you have a mind to; bring out all the fierceness that is in your heart.

Oedipus. That will I. I will not spare to speak my thoughts. Listen to what I have to say. It seems to me that you have helped to plot the deed; and, short of doing it with your own hands, have done the deed yourself. Had you eyesight I would declare that you alone had done it.

Tiresias. So that is what you say? I charge you to obey the decree that you your self have made, and from this day out to speak neither to these nor to me. You are the defiler of this land.

Oedipus. So brazen in your impudence? How do you hope to escape punishment?

Tiresias. I have escaped; my strength is in my truth.

Oedipus. Who taught you this? You never got it by your art.

Tiresias. You, because you have spurred me to speech against my will.

Oedipus. What speech? Speak it again that I may learn it better.

Tiresias. You are but tempting me—you understood me well enough.

Oedipus. No; not so that I can say I know it; speak it again.

Tiresias. I say that you are yourself the murderer that you seek.

Oedipus. You shall rue it for having spoken twice such outrageous words.

Tiresias. Would you that I say more that you may be still angrier?

Oedipus. Say what you will. I will not let it move me.

Tiresias. I say that you are living with your next of kin in unimagined shame.

Oedipus. Do you think you can say such things and never smart for it?

Tiresias. Yes, if there be strength in truth.

Oedipus. There is; yes—for everyone but you. But not for you that are maimed in ear and in eye and in wit.

Tiresias. You are but a poor wretch flinging taunts that in a little while everyone shall fling at you.

Oedipus. Night—endless night has covered you up so that you can neither hurt me nor any man that looks upon the sun.

Tiresias. Your doom is not to fall by me. Apollo is enough: it is his business to work out your doom.

Oedipus. Was it Creon that planned this or you yourself?

Tiresias. Creon is not your enemy; you are your own enemy.

Oedipus. Power, ability, position, you bear all burdens, and yet what envy you create! Great must that envy be if envy of my power in this town—a power put into my hands unsought—has made trusty Creon, my old friend Creon, secretly long to take that power from me; if he has suborned this scheming juggler, this quack and trickster, this man with eyes for his gains and blindness in his art. Come, come, where did you prove yourself a seer? Why did you say nothing to set the townsmen free when the riddling sphinx was here? Yet that riddle was not for the first-comer to read; it needed the skill of a seer. And none such had you! Neither found by help of birds, nor straight from any god. No, I came; I silenced her, I the ignorant Oedipus, it was I that found the answer in my mother wit, untaught by any birds. And it is I that you would pluck out of my place, thinking to stand close to Creon’s throne. But you and the plotter of all this shall mourn despite your zeal to purge the land. Were you not an old man, you had already learnt how bold you are and learnt it to your cost.

Chorus. Both this man’s words and yours, Oedipus, have been said in anger. Such words cannot help us here, nor any but those that teach us to obey the oracle.

Tiresias. King though you are, the right to answer when attacked belongs to both alike. I am not subject to you, but to Loxias; and therefore I shall never be Creon’s subject. And I tell you, since you have taunted me with blindness, that though you have your sight, you cannot see in what misery you stand, nor where you are living, nor with whom, unknowing what you do—for you do not know the stock you come of—you have been your own kin’s enemy be they living or be they dead. And one day a mother’s curse and father’s curse alike shall drive you from this land in dreadful haste with darkness upon those eyes. Therefore, heap your scorn on Creon and on my message if you have a mind to; for no one of living men shall be crushed as you shall be crushed.

Oedipus. Begone this instant! Away, away! Get thee from these doors!

Tiresias. I had never come but that you sent for me.

Oedipus. I did not know you were mad.

Tiresias. I may seem mad to you, but your parents thought me sane.

Oedipus. My parents! Stop! Who was my father?

Tiresias. This day shall you know your birth; and it will ruin you.

Oedipus. What dark words you always speak!

Tiresias. But are you not most skilful in the unravelling of dark words?

Oedipus. You mock me for that which made me great?

Tiresias. It was that fortune that undid you.

Oedipus. What do I care? For I delivered all this town.

Tiresias. Then I will go: boy, lead me out of this.

Oedipus. Yes, let him lead you. You take vexation with you.

Tiresias. I will go: but first I will do my errand. For frown though you may you cannot destroy me. The man for whom you look, the man you have been threatening in all the proclamations about the death of Laius, that man is here. He seems, so far as looks go, an alien; yet he shall be found a native Theban and shall nowise be glad of that fortune. A blind man, though now he has his. sight; a beggar, though now he is most rich; he shall go forth feeling the ground before him with his stick; so you go in and think on that, and if you find I am in fault say that I have no skill in prophecy.

Chorus. The Delphian rock has spoken out, now must a wicked mind

Planner of things I dare not speak and of this bloody wrack,

Pray for feet that run as fast as the four hoofs of the wind:

Cloudy Parnassus and the Fates thunder at his back.

That sacred crossing place of lines upon Parnassus’ head,

Lines drawn through North and South, and drawn through West and East,

That navel of the world bids all men search the mountain wood.

The solitary cavern, till they have found that infamous beast.

(Creon enters from the house.)

Creon. Fellow-citizens, having heard that King Oedipus accuses me of dreadful things, I come in my indignation. Does he think that he has suffered wrong from me in these present troubles, or anything that could lead to wrong, whether in word or deed? How can I live under blame like that? What life would be worth having if by you here, and by my nearest friends, called a traitor through the town?

Chorus. He said it in anger, and not from his heart out.

Creon. He said it was I put up the seer to speak those falsehoods.

Chorus. Such things were said.

Creon. And had he his right mind saying it?

Chorus. I do not know—I do not know what my masters do.

(Oedipus enters.)

Oedipus. What brought you here? Have you a face so brazen that you come to my house—you the proved assassin of its master—the certain robber of my crown. Come, tell me in the face of the gods what cowardice, or folly, did you discover in me that you plotted this? Did you think that I would not see what you were at till you had crept upon me, or seeing it would not ward it off? What madness to seek a throne, having neither friends nor followers.

Creon. Now, listen, hear my answer, and then you may with knowledge judge between us.

Oedipus. You are plausible, but waste words now that I know you.

Creon. Hear what I have to say. I can explain it all.

Oedipus. One thing you will not explain away—that you are my enemy.

Creon. You are a fool to imagine that senseless stubbornness sits well upon you.

Oedipus. And you to imagine that you can wrong a kinsman and escape the penalty.

Creon. That is justly said I grant you; but what is this wrong that you complain of?

Oedipus. Did you advise, or not, that I should send for that notorious prophet?

Creon. And I am of the same mind still.

Oedipus. How long is it then since Laius—

Creon. What, what about him?

Oedipus. Since Laius was killed by an unknown hand?

Creon. That was many years ago.

Oedipus. Was this prophet at his trade in those days?

Creon. Yes; skilled as now and in equal honour.

Oedipus. Did he speak of me at any time?

Creon. Never certainly when I was within earshot.

Oedipus. And did you make inquiry into the murder?

Creon. We made inquiry but learnt nothing.

Oedipus. And why did he not tell out his story then?

Creon. I do not know. Where I lack light I am silent.

Oedipus. This much at least you know and can say out.

Creon. What is that? If I know it I will say it.

Oedipus. That if he had not consulted you he would never have said that it was I who killed Laius.

Creon. You know best what he said; but now, question for question.

Oedipus. Question your fill—I cannot be proved guilty of that blood.

Creon. Answer me then. Are you not married to my sister?

Oedipus. That cannot be denied.

Creon. And do you not rule as she does? And with a like power?

Oedipus. I give her all she asks for.

Creon. And am not I the equal of you both?

Oedipus. Yes: and that is why you are so false a friend.

Creon. Not so; reason this out as I reason it, and first weigh this: who would prefer to lie awake amid terrors rather than to sleep in peace, granting that his power is equal in both cases. Neither I nor any sober-minded man. You give me what I ask and let me do what I want, but were I king I would have to do things I did not want to do. Is not influence and no trouble with it better than any throne, am I such a fool as to hunger after unprofitable honours? Now all are glad to see me, everyone wishes me well, all that want a favour from you ask speech of me—finding in that their hope. Why should I give up these things and take those? No wise mind is treacherous. I am no contriver of plots, and if another took to them he would not come to me for help. And in proof of this go to the Pythian Oracle, and ask if I have truly told what the gods said: and after that, if you have found that I have plotted with the Soothsayer, take me and kill me; not by the sentence of one mouth only—but of two mouths, yours and my own. But do not condemn me in a corner, upon some fancy and without proof. What right have you to declare a good man bad or a bad good? It is as bad a thing to cast off a true friend, as it is for a man to cast away his own life—but you will learn these things with certainty when the time comes; for time alone shows a just man; though a day can show a knave.

Chorus. King! He has spoken well, he gives himself time to think; a headlong talker does not know what he is saying.

Oedipus. The plotter is at his work, and I must counterplot headlong, or he will get his ends and I miss mine.

Creon. What will you do then? Drive me from the land?

Oedipus. Not so; I do not desire your banishment—but your death.

Creon. You are not sane.

Oedipus. I am sane at least in my own interest.

Creon. You should be in mine also.

Oedipus. No, for you are false.

Creon. But if you understand nothing?

Oedipus. Yet I must rule.

Creon. Not if you rule badly.

Oedipus. Hear him, O Thebes!

Creon. Thebes is for me also, not for you alone.

Chorus. Cease, princes: I see Jocasta coming out of the house; she comes just in time to quench the quarrel.

(Jocasta enters.)

Jocasta. Unhappy men! Why have you made this crazy uproar? Are you not ashamed to quarrel about your own affairs when the whole country is in trouble? Go back into the palace, Oedipus, and you, Creon, to your own house. Stop making all this noise about some petty thing.

Creon. Your husband is about to kill me—or to drive me from the land of my fathers.

Oedipus. Yes: for I have convicted him of treachery against me.

Creon. Now may I perish accursed if I have done such a thing.

Jocasta. For god’s love believe it, Oedipus. First, for the sake of his oath, and then for my sake, and for the sake of these people here.

Chorus (all). King, do what she asks.

Oedipus. What would you have me do?

Chorus. Not to make a dishonourable charge, with no more evidence than rumour, against a friend who has bound himself with an oath.

Oedipus. Do you desire my exile or my death?

Chorus. No, by Helios, by the first of all the gods, may I die abandoned by Heaven and earth if I have that thought. What breaks my heart is that our public griefs should be increased by your quarrels.

Oedipus. Then let him go, though I am doomed thereby to death or to be thrust dishonoured from the land; it is your lips, not his, that move me to compassion; wherever he goes my hatred follows him.

Creon. You are as sullen in yielding as you were vehement in anger, but such natures are their own heaviest burden.

Oedipus. Why will you not leave me in peace and begone?

Creon. I will go away; what is your hatred to me; in the eyes of all here I am a just man. [He goes.

Chorus. Lady, why do you not take your man in to the house?

Jocasta. I will do so when I have learned what has happened.

Chorus. The half of it was blind suspicion bred of talk; the rest the wounds left by injustice.

Jocasta. It was on both sides?

Chorus. Yes.

Jocasta. What was it?

Chorus. Our land is vexed enough. Let the thing alone now that it is over.

Jocasta. In the name of the gods, king, what put you in this anger?

Oedipus. I will tell you; for I honour you more than these men do. The cause is Creon and his plots against me.

Jocasta. Speak on, if you can tell clearly how this quarrel arose.

Oedipus. He says that I am guilty of the blood of Laius.

Jocasta. On his own knowledge, or on hearsay?

Oedipus. He has made a rascal of a seer his mouthpiece.

Jocasta. Do not fear that there is truth in what he says. Listen to me, and learn to your comfort that nothing born of woman can know what is to come. I will give you proof of that. An oracle came to Laius once, I will not say from Phoebus, but from his ministers, that he was doomed to die by the hand of his own child sprung from him and me. When his child was but three days old Laius bound its feet together and had it thrown by sure hands upon a trackless mountain; and when Laius was murdered at the place where three highways meet, it was, or so at least the rumour says, by foreign robbers. So Apollo did not bring it about that the child should kill its father, nor did Laius die in the dreadful way he feared by his child’s hand. Yet that was how the message of the seers mapped out the future. Pay no attention to such things. What the god would show he will need no help to show it, but bring it to light himself.

Oedipus. What restlessness of soul, lady, has come upon me since I heard you speak, what a tumult of the mind!

Jocasta. What is this new anxiety? What has startled you?

Oedipus. You said that Laius was killed where three highways meet.

Jocasta. Yes: that was the story.

Oedipus. And where is the place?

Jocasta. In Phocis where the road divides branching off to Delphi and to Daulia.

Oedipus. And when did it happen? How many years ago?

Jocasta. News was published in this town just before you came into power.

Oedipus. O Zeus! What have you planned to do unto me?

Jocasta. He was tall; the silver had just come into his hair; and in shape not greatly unlike to you.

Oedipus. Unhappy that I am! It seems that I have laid a dreadful curse upon myself, and did not know it.

Jocasta. What do you say? I tremble when I look on you, my king.

Oedipus. And I have a misgiving that the seer can see indeed. But I will know it all more clearly, if you tell me one thing more.

Jocasta. Indeed, though I tremble I will answer whatever you ask.

Oedipus. Had he but a small troop with him; or did he travel like a great man with many followers?

Jocasta. There were but five in all—one of them a herald; and there was one carriage with Laius in it.

Oedipus. Alas! It is now clear indeed. Who was it brought the news, lady?

Jocasta. A servant—the one survivor.

Oedipus. Is he by chance in the house now?

Jocasta. No; for when he found you reigning instead of Laius he besought me, his hand clasped in mine, to send him to the fields among the cattle that he might be far from the sight of this town; and I sent him. He was a worthy man for a slave and might have asked a bigger thing.

Oedipus. I would have him return to us without delay.

Jocasta. Oedipus, it Is easy. But why do you ask this?

Oedipus. I fear that I have said too much, and therefore I would question him.

Jocasta. He shall come, but I too have a right to know what lies so heavy upon your heart, my king.

Oedipus. Yes: and it shall not be kept from you; now that my fear has grown so heavy. Nobody is more to me than you, nobody has the same right to learn my good or evil luck. My father was Polybius of Corinth—my mother the Dorian Merope, and I was held the foremost man in all that town until a thing happened—a thing to startle a man, though not to make him angry as it made me. We were sitting at the table, and a man who had drunk too much cried out that I was not my father’s son—and I, though angry, restrained my anger for that day; but the next day went to my father and my mother and questioned them. They were indignant at the taunt and that comforted me—and yet the man’s words rankled, for they had spread a rumour through the town. Without consulting my father or my mother I went to Delphi, but Phoebus told me nothing of the thing for which I came, but much of other things—things of sorrow and of terror: that I should live in incest with my mother, and beget a brood that men would shudder to look upon; that I should be my father’s murderer. Hearing those words I fled out of Corinth, and from that day have but known where it lies when I have found its direction by the stars. I sought where I might escape those infamous things—the doom that was laid upon me. I came in my flight to that very spot where you tell me this king perished. Now, lady, I will tell you the truth. When I had come close up to those three roads, I came upon a herald, and a man like him you have described seated in a carriage. The man who held the reins and the old man himself would not give me room, but thought to force me from the path, and I struck the driver In my anger. The old man, seeing what I had done, waited till I was passing him and then struck me upon the head. I paid him back in full, for I knocked him out of the carriage with a blow of my stick. He rolled on his back, and after that I killed them all. If this stranger were indeed Laius, is there a more miserable man in the world than the man before you? Is there a man more hated of Heaven? No stranger, no citizen, may receive him into his house, not a soul may speak to him, and no mouth but my own mouth has laid this curse upon me. Am I not wretched? May I be swept from this world before I have endured this doom!

Chorus. These things, O King, fill us with terror; yet hope till you speak with him that saw the deed, and have learnt all.

Oedipus. Till I have learnt all, I may hope. I await the man that is coming from the pastures.

Jocasta. What is it that you hope to learn?

Oedipus. I will tell you. If his tale agrees with yours, then I am clear.

Jocasta. What tale of mine?

Oedipus. He told you that Laius met his death from robbers; if he keeps to that tale now and speaks of several slayers I am not the slayer. But if he says one lonely wayfarer, then beyond a doubt the scale dips to me.

Jocasta. Be certain of this much at least, his first tale was of robbers. He cannot revoke that tale—the city heard it and not I alone. Yet, if he should somewhat change his story, king, at least he cannot make the murder of Laius square with prophecy; for Loxius plainly said of Laius that he would die by the hand of my child. That poor innocent did not kill him, for it died before him. Therefore from this out I would not for all divination can do so much as look to my right hand or to my left hand, or fear at all.

Oedipus. You have judged well; and yet for all that, send and bring this peasant to me.

Jocasta. I will send without delay. I will do all that you would have of me—but let us come in to the house.

Chorus

For this one thing above all I would be praised as a man,

That in my words and my deeds I have kept those laws in mind

Olympian Zeus, and that high clear Empyrean,

Fashioned, and not some man or people of mankind,

Even those sacred laws nor age nor sleep can blind.

A man becomes a tyrant out of insolence,

He climbs and climbs, until all people call him great,

He seems upon the summit, and God flings him thence;

Yet an ambitious man may lift up a whole State,

And in his death be blessed, in his life fortunate.

And all men honour such; but should a man forget

The holy Images, the Delphian Sybil’s trance

And the world’s navel stone, and not be punished for it

And seem most fortunate, or even blessed perchance,

Why should we honour the gods, or join the sacred dance?

(Jocasta enters from the palace.)

Jocasta. It has come into my head, citizens of Thebes, to visit every altar of the gods, a wreath in my hand and a dish of incense. For all manner of alarms trouble the soul of Oedipus, who instead of weighing new oracles by old, like a man of sense, is at the mercy of every mouth that speaks terror. Seeing that my words are nothing to him, I cry to you, Lysian Apollo, whose altar is the first I meet: I come, a suppliant, bearing symbols of prayer; O make us clean, for now we are all afraid, seeing him afraid, even as they who see the helmsman afraid.

(Enter Messenger).

Messenger. May I learn from you, strangers, where is the home of King Oedipus? Or better still, tell me where he himself is, if you know.

Chorus. This is his house, and he himself, stranger, is within it, and this lady is the mother of his children.

Messenger. Then I call a blessing upon her, seeing what man she has married.

Jocasta. May god reward those words with a like blessing, stranger. But what have you come to seek or to tell?

Messenger. Good news for your house, lady, and for your husband.

Jocasta. What news? From whence have you come?

Messenger. From Corinth, and you will rejoice at the message I am about to give you; yet, maybe, it will grieve you.

Jocasta. What is it? How can it have this double power?

Messenger. The people of Corinth, they say, will take him for king.

Jocasta. How then? Is old Polybius no longer on the throne?

Messenger. No. He is in his tomb.

Jocasta. What do you say? Is Polybius dead, old man?

Messenger. May I drop dead if it is not the truth.

Jocasta. Away! Hurry to your master with this news. O oracle of the gods, where are you now? This is the man whom Oedipus feared and shunned lest he should murder him, and now this man has died a natural death, and not by the hand of Oedipus.

(Enter Oedipus.)

Oedipus. Jocasta, dearest wife, why have you called me from the house?

Jocasta. Listen to this man, and judge to what the oracles of the gods have come.

Oedipus. And he—who may he be? And what news has he?

Jocasta. He has come from Corinth to tell you that your father, Polybius, is dead.

Oedipus. How, stranger? Let me have it from your own mouth.

Messenger. If I am to tell the story, the first thing is that he is dead and gone.

Oedipus. By some sickness or by treachery?

Messenger. A little thing can bring the aged to their rest.

Oedipus. Ah! He died, it seems, from sickness?

Messenger. Yes; and of old age.

Oedipus. Alas! Alas! Why, indeed, my wife, should one look to that Pythian seer, or to the birds that scream above our heads? For they would have it that I was doomed to kill my father. And now he is dead—hid already beneath the earth. And here am I—who had no part in it, unless indeed he died from longing for me. If that were so, I may have caused his death; but Polybius has carried the oracles with him into Hades—the oracles as men have understood them—and they are worth nothing.

Jocasta. Did I not tell you so, long since?

Oedipus. You did, but fear misled me.

Jocasta. Put this trouble from you.

Oedipus. Those bold words would sound better, were not my mother living. But as it is—I have some grounds for fear; yet you have said well.

Jocasta. Yet your father’s death is a sign that all is well.

Oedipus. I know that: but I fear because of her who lives.

Messenger. Who is this woman who makes you afraid?

Oedipus. Merope, old man, the wife of Polybius.

Messenger. What is there in her to make you afraid?

Oedipus. A dreadful oracle sent from Heaven, stranger.

Messenger. Is it a Secret, or can you speak it out?

Oedipus. Loxius said that I was doomed to marry my own mother, and to shed my father’s blood. For that reason I fled from my house in Corinth; and I did right though there is great comfort in familiar faces.

Messenger. Was it indeed for that reason that you went into exile?

Oedipus. I did not wish, old man, to shed my father’s blood.

Messenger. King, have I not freed you from that fear?

Oedipus. You shall be fittingly rewarded.

Messenger. Indeed, to tell the truth, it was for that I came; to bring you home and be the better for it———

Oedipus. No! I will never go to my parents’ home.

Messenger. Ah, my son, it is plain enough, you do not know what you do.

Oedipus. How, old man? For the gods’ love, tell me.

Messenger. If for these reasons you shrink from going home.

Oedipus. I am afraid lest Phoebus has spoken true.

Messenger. You are afraid of being made guilty through Merope?

Oedipus. That is my constant fear.

Messenger. A vain fear.

Oedipus. How so, if I was born of that father and mother?

Messenger. Because they were nothing to you in blood.

Oedipus. What do you say? Was Polybius not my father?

Messenger. No more nor less than myself.

Oedipus. How can my father be no more to me than you who are nothing to me?

Messenger. He did not beget you any more than I.

Oedipus. No? Then why did he call me his son?

Messenger. He took you as a gift from these hands of mine.

Oedipus. How could he love so dearly what came from another’s hands?

Messenger. He had been childless.

Oedipus. If I am not your son, where did you get me?

Messenger. In a wooded valley of Cythaeron.

Oedipus. What brought you wandering there?

Messenger. I was in charge of mountain sheep.

Oedipus. A shepherd—a wandering, hired man.

Messenger. A hired man who came just in time.

Oedipus. Just in time—had it come to that?

Messenger. Have not the cords left their marks upon your ankles?

Oedipus. Yes, that is an old trouble.

Messenger. I took your feet out of the spancel.

Oedipus. I have had those marks from the cradle.

Messenger. They have given you the name you bear.

Oedipus. Tell me, for the gods’ sake, was that deed my mother’s or my father’s?

Messenger. I do not know—he who gave you to me knows more of that than I.

Oedipus. What? You had me from another? You did not chance on me yourself?

Messenger. No. Another shepherd gave you to me.

Oedipus. Who was he? Can you tell me who he was?

Messenger. I think that he was said to be of Laius’ household.

Oedipus. The king who ruled this country long ago?

Messenger. The Same—the man was herdsman in his service.

Oedipus. Is he alive, that I might speak with him?

Messenger. You people of this country should know that.

Oedipus. Is there anyone here present who knows the herd he speaks of? Anyone who has seen him in the town pastures. The hour has come when all must be made clear.

Chorus. I think he is the very herd you sent for but now, Jocasta can tell you better than I.

Jocasta. Why ask about that man? Why think about him? Why waste a thought on what this man has said? What he has said is of no account.

Oedipus. What, with a clue like that in my hands and fail to find out my birth?

Jocasta. For God’s sake, if you set any value upon your life, give up this search—my misery is enough.

Oedipus. Though I be proved the son of a slave, yes, even of three generations of slaves, you cannot be made base born.

Jocasta. Yet, hear me, I implore you. Give up this search.

Oedipus. I will not hear of anything but searching the whole thing out.

Jocasta. I am only thinking of your good—I have advised you for the best.

Oedipus. Your advice makes me impatient.

Jocasta. May you never come to know who you are, unhappy man!

Oedipus. Go, someone, bring the herdsman here—and let that woman glory in her noble blood.

Jocasta. Alas, alas, miserable man! Miserable! That is all that I can call you now or forever. [She goes out.

Chorus. Why has the lady gone, Oedipus, in such a transport of despair? Out of this silence will burst a storm of sorrows.

Oedipus. Let come what will. However lowly my origin I will discover it. That woman, with all a woman’s pride, grows red with shame at my base birth. I think my self the child of Good Luck, and that the years are my foster-brothers. Sometimes they have set me up, and sometimes thrown me down, but he that has Good Luck for mother can suffer no dishonour. That is my origin, nothing can change it, so why should I renounce this search into my birth?

Chorus

Oedipus’ nurse, mountain of many a hidden glen,

Be honoured among men;

A famous man, deep thoughted, and his body strong;

Be honoured in dance and song.

Who met in the hidden glen? Who let his fancy run

Upon nymph of Helicon?

Lord Pan or Lord Apollo or the mountain Lord,

By the Bacchantes adored?

Oedipus. If I, who have never met the man, may venture to say so, I think that the herdsman we await approaches; his venerable age matches with this stranger’s, and I recognise as servants of mine those who bring him. But you, if you have seen the man before, will know the man better than I.

Chorus. Yes, I know the man who is coming; he was indeed in Laius’ service, and is still the most trusted of the herdsmen.

Oedipus. I ask you first, Corinthian stranger, is this the man you mean?

Messenger. He is the very man.

Oedipus. Look at me, old man! Answer my questions. Were you once in Laius’ service?

Herdsman. I was: not a bought slave, but reared up in the house.

Oedipus. What was your work—your manner of life?

Herdsman. For the best part of my life I have tended flocks.

Oedipus. Where, mainly?

Herdsman. Cythaeron or its neighbourhood.

Oedipus. Do you remember meeting with this man there?

Herdsman. What man do you mean?

Oedipus. This man. Did you ever meet him?

Herdsman. I cannot recall him to mind.

Messenger. No wonder in that, master; but I will bring back his memory. He and I lived side by side upon Cythaeron. I had but one flock and he had two. Three full half-years we lived there, from spring to autumn, and every winter I drove my flock to my own fold, while he drove his to the fold of Laius. Is that right? Was it not so?

Herdsman. True enough; though it was long ago.

Messenger. Come, tell me now—do you remember giving me a boy to rear as my own foster-son?

Herdsman. What are you saying? Why do you ask me that?

Messenger. Look at that man, my friend, he is the child you gave me.

Herdsman. A plague upon you! Cannot you hold your tongue?

Oedipus. Do not blame him, old man; your own words are more blameable.

Herdsman. And how have I offended, master?

Oedipus. In not telling of that boy he asks of.

Herdsman. He speaks from ignorance, and does not know what he is saying.

Oedipus. If you will not speak with a good grace you shall be made to speak.

Herdsman. Do not hurt me for the love of God, I am an old man.

Oedipus. Someone there, tie his hands behind his back.

Herdsman. Alas! Wherefore? What more would you learn?

Oedipus. Did you give this man the child he speaks of?

Herdsman. I did: would I had died that day!

Oedipus. Well, you may come to that unless you speak the truth.

Herdsman. Much more am I lost if I speak it.

Oedipus. What! Would the fellow make more delay?

Herdsman. No, no. I said before that I gave it to him.

Oedipus. Where did you come by it? Your own child, or another?

Herdsman. It was not my own child—I had it from another.

Oedipus. From any of those here? From what house?

Herdsman. Do not ask any more, master; for the love of God do not ask.

Oedipus. You are lost if I have to question you again.

Herdsman. It was a child from the house of Laius.

Oedipus. A slave? Or one of his own race?

Herdsman. Alas! I am on the edge of dreadful words.

Oedipus. And I of hearing: yet hear I must.

Herdsman. It was Said to have been his own child. But your lady within can tell you of these things best.

Oedipus. How? It was she who gave it to you?

Herdsman. Yes, king.

Oedipus. To what end?

Herdsman. That I should make away with it.

Oedipus. Her own child?

Herdsman. Yes: from fear of evil prophecies.

Oedipus. What prophecies?

Herdsman. That he should kill his father.

Oedipus. Why, then, did you give him up to this old man?

Herdsman. Through pity, master, believing that he would carry him to whatever land he had himself come from—but he saved him for dreadful misery; for if you are what this man says, you are the most miserable of all men.

Oedipus. O! O! All brought to pass! All truth! Now O Light, may I look my last upon you, having been found accursed in bloodshed, accursed in marriage, and in my coming into the world accursed!

Chorus

What can the shadow-like generations of man attain

But build up a dazzling mockery of delight that under their touch dissolves again?

Oedipus seemed blessed, but there is no man blessed amongst men.

Oedipus overcame the woman-breasted Fate;

He seemed like a strong tower against Death and first among the fortunate;

He sat upon the ancient throne of Thebes and all men called him great.

But, looking for a marriage bed, he found the bed of his birth,

Tilled the field his father had tilled, cast seed into the same abounding earth;

Entered through the door that had sent him wailing forth.

Begetter and begot as one! How could that be hid?

What darkness cover up that marriage bed? Time watches, he is eagle-eyed,

And all the works of man are known and every soul is tried.

Would you had never come to Thebes, nor to this house,

Nor riddled with the woman-breasted Fate, beaten off death and succoured us,

That I had never raised this song, heart-broken Oedipus.

Second Messenger [coming from the house]. Friends and kinsmen of this house! What deeds must you look upon, what burden of sorrow bear, if true to race you still love the House of Labdicus. For not Istar nor Phasis could wash this house clean, so many misfortunes have been brought upon it, so many has it brought upon itself, and those misfortunes are always the worst that a man brings upon himself.

Chorus. Great already are the misfortunes of this house, and you bring us a new tale.

Second Messenger. A short tale in the telling; Jocasta, our queen, is dead.

Chorus. Alas, miserable woman, how did she die?

Second Messenger. By her own hand. It cannot be as terrible to you as to one that saw it with his eyes, yet so far as words can serve, you shall see it. When she had come into the vestibule, she ran half crazed towards her marriage bed, clutching at her hair with the fingers of both hands, and once within the chamber dashed the doors together behind her. Then called upon the name of Laius, long since dead, remembering that son who killed the father and upon the mother begot an accursed race. And wailed because of that marriage wherein she had borne a twofold race—husband by husband, children by her child. Then Oedipus with a shriek burst in and rushing here and there asked for a sword, asked where he would find the wife that was no wife but a mother who had borne his children and himself. Nobody answered him, we all stood dumb; but super natural power helped him for, with a dreadful shriek, as though beckoned, he sprang at the double doors, drove them in, burst the bolts out of their sockets, and rushed into the room. There we saw the woman hanging in a swinging halter, and with a terrible cry he loosened the halter from her neck. When that unhappiest woman lay stretched upon the ground, we saw another dreadful sight. He dragged the golden brooches from her dress and lifting them struck them upon his eyeballs, crying out, ‘You have looked enough upon those you ought never to have looked upon, failed long enough to know those that you should have known; henceforth you shall be dark’. He struck his eyes, not once, but many times, lifting his hands and speaking such or like words. The blood poured down and not with a few slow drops, but all at once over his beard in a dark shower as it were hail.

Such evils have come forth from the deeds of those two and fallen not on one alone but upon husband and wife. They inherited much happiness, much good fortune; but to-day, ruin, shame, death, and loud crying, all evils that can be counted up, all, all are theirs.

Chorus. Is he any quieter?

Second Messenger. He cries for someone to unbar the gates and to show to all the men of Thebes his father’s murderer, his mother’s—the unholy word must not be spoken. It is his purpose to cast himself out of the land that he may not bring all this house under his curse. But he has not the strength to do it. He must be supported and led away. The curtain is parting; you are going to look upon a sight which even those who shudder must pity.

(Enter Oedipus.)

Oedipus. Woe, woe is me! Miserable, miserable that I am! Where am I? Where am I going? Where am I cast away? Who hears my words?

Chorus. Cast away indeed, dreadful to the sight of the eye, dreadful to the ear.

Oedipus. Ah, friend, the only friend left to me, friend still faithful to the blind man! I know that you are there blind though I am, I recognise your voice.

Chorus. Where did you get the courage to put out your eyes?

What unearthly power drove you to that?

Oedipus. Apollo, friends, Apollo, but it was my own hand alone, wretched that I am, that quenched these eyes.

Chorus. You were better dead than blind.

Oedipus. No, it is better to be blind. What sight is there that could give me joy? How could I have looked into the face of my father when I came among the dead, aye, or on my miserable mother, since against them both I sinned such things that no halter can punish. And what to me this spectacle, town, statue, wall, and what to me this people, since I, thrice wretched, I noblest of Theban men, have doomed myself to banishment, doomed myself when I commanded all to thrust out the unclean thing.

Chorus. It had indeed been better if that herdsman had never taken your feet out of the bonds or brought you back to life.

Oedipus. O three roads, O secret glen; O coppice and narrow way where three roads met; you that drank up the blood I spilt, the blood that was my own, my father’s blood; remember what deeds I wrought for you to look upon, and then, when I had come hither, the new deeds that I wrought. O marriage bed that gave me birth and after that gave children to your child, creating an incestuous kindred of fathers, brothers, sons, wives, and mothers. Yes, all the shame and the uncleanness that I have wrought among men.

Chorus. For all my pity I shudder and turn away.

Oedipus. Come near, condescend to lay your hands upon a wretched man; listen, do not fear. My plague can touch no man but me. Hide me somewhere out of this land for God’s sake, or kill me, or throw me into the sea where you shall never look upon me more.

(Enter Creon and attendants.)

Chorus. Here Creon comes at a fit moment, you can ask of him what you will, help or counsel, for he is now in your place. He is king.

Oedipus. What can I say to him? What can I claim, having been altogether unjust to him?

Creon. I have not come in mockery, Oedipus, nor to reproach you. Lead him in to the house as quickly as you can. Do not let him display his misery before strangers.

Oedipus. I must obey, but first, since you have come in so noble a spirit, you will hear me.

Creon. Say what you will.

Oedipus. I know that you will give her that lies within such a tomb as befits your own blood, but there is something more, Creon. My sons are men and can take care of themselves, but my daughters, my two unhappy daughters, that have ever eaten at my own table and shared my food, watch over my daughters, Creon. If it is lawful, let me touch them with my hands. Grant it, prince, grant it, noble heart. I would believe could I touch them that I still saw them.

But do I hear them sobbing? Has Creon pitied me and sent my children, my darlings? Has he done this?

Creon. Yes, I ordered it, for I know how greatly you have always loved them.

Oedipus. Then may you be blessed, and may Heaven be kinder to you than it has been to me. My children, where are you? Come hither—hither—come to the hands of him whose mother was your mother; the hands that put out your father’s eyes, eyes once as bright as your own; his, who understanding nothing, seeing nothing, be came your father by her that bore him. I weep when I think of the bitter life that men will make you live, and the days that are to come. Into what company dare you go, to what festival, but that you shall return home from it not sharing in the joys, but bathed in tears. When you are old enough to be married, what man dare face the reproach that must cling to you and to your children? What misery is there lacking? Your father killed his father, he begat you at the spring of his own being, offspring of her that bore him. That is the taunt that would be cast upon you and on the man that you should marry. That man is not alive; my children, you must wither away in barrenness. Ah, son of Menoeceus, listen. Seeing that you are the only father now left to them, for we their parents are lost, both of us lost, do not let them wander in beggary—are they not your own kindred?—do not let them sink down into my misery. No, pity them, seeing them utterly wretched in helpless childhood if you do not protect them. Show me that you promise, generous man, by touching me with your hand, [Creon touches him.] My children, there is much advice that I would give you were you but old enough to under stand, but all I can do now is bid you pray that you may live wherever you are let live, and that your life be happier than your father’s.

Creon. Enough of tears. Pass into the house.

Oedipus. I will obey, though upon conditions.

Creon. Conditions?

Oedipus. Banish me from this country. I know that nothing can destroy me, for I wait some incredible fate; yet cast me upon Cythaeron, chosen by my father and my mother for my tomb.

Creon. Only the gods can say yes or no to that.

Oedipus. No, for I am hateful to the gods.

Creon. If that be so you will get your wish the quicker. They will banish that which they hate.

Oedipus. Are you certain of that?

Creon. I would not say it if I did not mean it.

Oedipus. Then it is time to lead me within.

Creon. Come, but let your children go.

Oedipus. No, do not take them from me.

Creon. Do not seek to be master; you won the mastery but could not keep it to the end.

[He leads Oedipus into the palace, followed by Ismene, Antigone, and attendants.

Chorus

Make way for Oedipus. All people said

‘That is a fortunate man’;

And now what storms are beating on his head?

Call no man fortunate that is not dead.

The dead are free from pain.

THE MUSIC FOR THE CHORUS

THE MUSIC FOR THE CHORUS

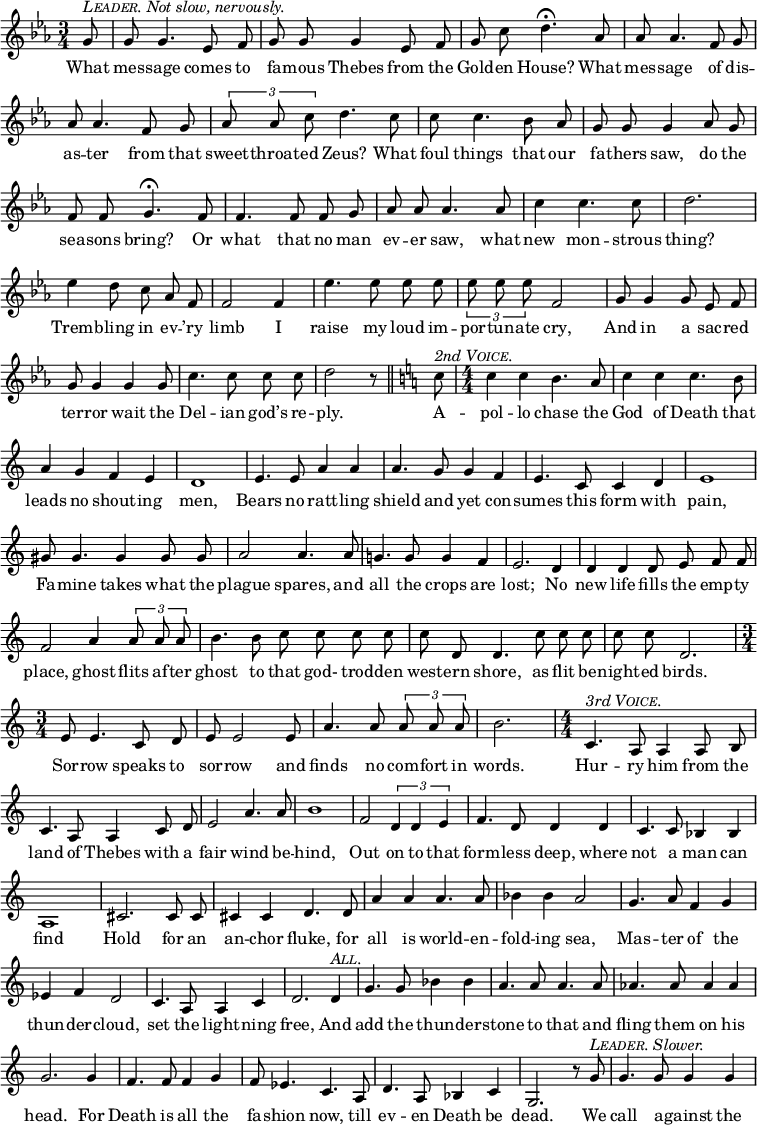

This music was used at the production of the play in the Abbey Theatre. It was written for a Leader and five others. The Leader’s voice should be of tenor quality, the Second Voice a baritone, the Third Voice a bass, the other voices—and there can be as many as the producer likes—should be bass. The music should not be sung in strict time. If necessary, one of the Chorus can have a small flute or whistle and softly play a note or two before each chorus begins.

FIRST CHORUS.

SECOND CHORUS.

![\relative d' {

\set Staff.midiInstrument = "cello"

\clef treble

\key bes \major \time 2/4

\numericTimeSignature

\override Score.BarNumber #'break-visibility = #'#(#f #f #f)

\partial 8

{ \autoBeamOff

d8^\markup { \italic { \smallCaps All. Slowly and heavily. } } d4. d8 d4 d g g g2\fermata d4^\markup { \italic { 3rd \smallCaps Voice. } } d8 d

\times 2/3 {ees4 ees ees} d2 d8 d4 d8 d4 d c c c2

c4 c8 c ees4 ees d2 g4. g8 bes4 bes a4. a8 %end of score from prev.

a4 a8 a aes4 aes aes8 aes g4 f4 f8 f f4 f f8 f ees4

d c bes a g4. \bar "||" \key c \minor

g'8^\markup { \italic \smallCaps Leader. } g4. g8 g4 g c4. c8

c4. c8 c4. c8 c4 g aes2 g4 g8 g c4. c8

ees4. c8 d4. d8 d4 d d4. d8 c8 c c c

des4. des8 des8 des c c aes bes c8. g16 g8 g g g

aes4 aes f ees8 f g4 f ees des c2 \bar "||" }

\addlyrics {

The Del -- phian rock has spok -- en out, now must a

wicked __ _ _ mind Plan -- ner of things I dare not speak

and of the blood -- y wrack, Pray for feet that run as %end lyrics from prev.

fast as the four hoofs of the wind: Cloud -- y Par -- nass -- us and the Fates

thun -- der at his back.

That sa -- cred cross -- ing place of

lines up -- on Par -- nass -- us’ head, Lines drawn thro’ North and

South, and drawn through West and East, That na -- vel of the

world bids all men search the moun -- tain wood, The so -- li -- ta -- ry

ca -- vern, till they have found that infa -- mous beast.

}

\addlyrics { _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ [that

in -- fa -- mous] _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _

_ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _

_ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _

_ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _

_ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _

_ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _

_ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _

_ _ _ _ _ _ _ [ev -- il] }

}](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/e/8/e8pqny7ebk0oneodcfl5v02trz1rdor/e8pqny7e.png)

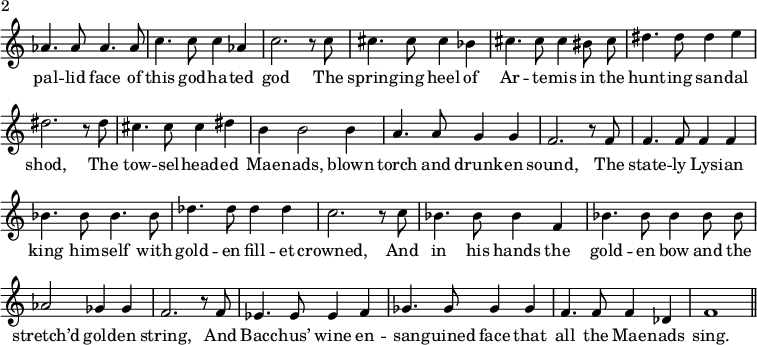

THIRD CHORUS.

FOURTH CHORUS.

FIFTH CHORUS.

N.B.—The final chorus was spoken, not sung, by the Leader.

Printed in Great Britain by R. & R. Clark, Limited, Edinburgh.

BY W. B. YEATS

THE COLLECTED WORKS

Attractively bound in green cloth, with

cover design by Charles Rickett

Crown 8vo. 10s. 6d. net each

LATER POEMS.

PLAYS IN PROSE AND VERSE.

PLAYS AND CONTROVERSIES.

ESSAYS.

EARLY POEMS AND STORIES.

AUTOBIOGRAPHIES: REVERIES OVER CHILDHOOD AND YOUTH, AND THE TREMBLING OF THE VEIL. Illustrated.

STORIES OF RED HANRAHAN AND THE SECRET ROSE. With Illustrations by Norah McGuinness. 8vo. 10s. 6d. net.

STORIES OF RED HANRAHAN; THE SECRET ROSE; ROSA ALCHEMICA. Crown 8vo. 4s. 6d. net.

RESPONSIBILITIES AND OTHER POEMS. Crown 8vo. 4s. 6d, net.

THE WILD SWANS AT COOLE. Poems. Crown 8vo. 3s. 6d. net.

THE TOWER. Crown 8vo. 6s. net.

SOPHOCLES’ KING OEDIPUS. A Version for the Modern Stage. Crown 8vo.

SOPHOCLES’ OEDIPUS COLONEUS. Crown 8vo.

FOUR PLAYS FOR DANCERS. Illustrated by Edmund Dulac. Fcap. 4to. 5s. net.

THE PLAYER QUEEN. Globe 8vo. 1s. net.

THE CUTTING OF AN AGATE. Essays. Crown 8vo. 4s. 6d. net.

REVERIES OVER CHILDHOOD AND YOUTH. Illustrated. Crown 8vo. 4s. 6d. net.

MACMILLAN AND CO., LTD., LONDON.

![]()

![]() This work is a translation and has a separate copyright status to the applicable copyright protections of the original content.

This work is a translation and has a separate copyright status to the applicable copyright protections of the original content.

| Original: |

This work was published before January 1, 1929, and is in the public domain worldwide because the author died at least 100 years ago.

Public domainPublic domainfalsefalse |

|---|---|

| Translation: |

This work is in the public domain in the United States because it was published in 1928, before the cutoff of January 1, 1929. The longest-living author of this work died in 1939, so this work is in the public domain in countries and areas where the copyright term is the author's life plus 84 years or less. This work may be in the public domain in countries and areas with longer native copyright terms that apply the rule of the shorter term to foreign works.

Public domainPublic domainfalsefalse |