If I were a woman I should always be a little irritated with any story which shows two women in love with the same man. Miss May Sinclair in her new novel does not mind how much she annoys her own sex. She shows us no fever than three women engaged in this competition, and they are sisters. True, there was not much choice for them in their lonely moorland village, which contained a young doctor and no other eligible man. Of this fellow Rowcliffe we are told that "his eyes were liable in repose to become charged with a curious and engaging pathos," an attraction which had broken many hearts before the story opened, and gave to their owner a great sense of confidence in himself. This set me against him at the start, but the three sisters, as I said, were not in a position to be fastidious. Mary's love for him was of the social-domestic kind; Gwenda's was spiritual; Alice's frankly physical. Though alleged to be "as good as gold," Alice, the youngest of The Three Sisters (Hutchinson), was one of those hysterical women who threaten to die or go mad unless they get married—a very unpleasant fact for a young doctor to have to discuss with her sister, and for us to read about. Indeed, if I were to tell in all its incredible crudity the story of the relations of this gently-bred girl with the drunken farmer who, to her knowledge, had previously betrayed her own servant-girl, I think even Miss Sinclair would be revolted. Her exposure of certain secret things which common decency agrees to leave in silence is a treachery to her sex, not excusable on grounds of physiological interest; and I, for one, who was loud in my praise of the fine qualities of her great romance, The Divine Fire, confess to a sense of almost personal sorrow that such high gifts as hers, which still show no trace of decline in craftsmanship, should have suffered so much taint. I sincerely hope that the noble work she is now doing with the Red Cross at the front—where the best wishes of her many friends follow her—may make more clear the claim that is laid upon her to devote her exceptional powers as a writer to the higher issues of life and death; or, at the least, to something cleaner and sweeter than the morbid atmosphere of her present theme.

It has been my private conviction that the most depressing and shuddersome of all natural prospects is the wide expanse of mud and slime to be found at low water in the estuary of a tidal river. Such scenes have always been singularly abhorrent to me. Mr. "Adrian Ross" appears to share this feeling, for out of one of them he has made the novel and very effective setting for his bogie-tale, The Hole of the Pit (Arnold). It is a story of the Civil Wars, though these have less to do with the action than the uncivil and very gruesome war waged between the Lord of Deeping Castle and the Unseen Thing that lived in the Pit. The Pit itself is real joy. It was covered always by the tide, but could be distinguished by a darker shadow on the surface of the sluggish stream, a shadow streaked at times by wavering bands of greyish slime, strangely agitated... There were smells, too, dank, sodden, drowned smells that came in upon the sea mist. Moreover, Deeping Castle I can only describe as an eligible residence for the immortal Fat Boy. It was built right upon the water, within convenient distance, as the auctioneers say, of the Pit; and between the two of them your flesh is made to creep more than you would believe possible. As for the great scene where the Thing finally gets out of the Pit, and comes slobbering and sucking round the castle walls—I cannot hope to convey to you the horror of it. Perhaps you may feel with me that Mr. Ross has been at times a little too confident that the undoubted thrill of his bogie would save it from being unintentionally funny. I confess I did laugh once in the wrong place. But everywhere else I shivered with the fearful joy that only the best in this kind can produce.

I remember that I have before this admired the mixture of cheerful cynicism and dry humour that is the speciality of Mr. Max Ritternberg. He has shown it again in Every Man His Price (Methuen), but hardly, I think, to quite the same effect as formerly. My feeling about the book was that it started with a first-class idea for a plot of comedy and intrigue, but that the author, instead of being contented with this, wanted to give us a novel of character-development on the grand scale, and somewhat spoilt his work in the attempt. The earlier chapters could hardly have been better. There was a real snap in the struggle between the English hero, Hilary Warde, who had nearly perfected a system of wireless telephony, and the Berlin magnates who wished to bluff him out of the results. As I say, I liked these early scenes and some others subsequently that dealt with rather sensational finance (it always cheers me up when the hero makes half-a-million pounds in a single chapter!) better than those that had to do with Warde's domestic entanglements and the deterioration of his character. And the climax seemed inadequate to the point of bathos. But there is much in the tale to enjoy; and you might read it if only for a vivid word-picture of what Berlin used to be like before the beginning of the great debacle. This has now an interest almost historical.

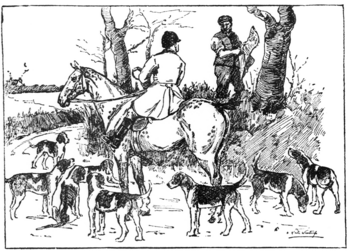

Hedger. "There's awful accounts in this 'ere paper of they Germans—seems there's some people as don't 'old nothing sacred."

Huntsman. "Ah! you may say so! And it ain't only Germans. Only last night I found as fine a dog-fox as ever I see with a bullet-wound through 'is 'eart!"

"TURKISH AMBASSADOR LEAVES BORDEAUX.

The Turkish Ambassador left Paris yesterday on a visit to Biarritz. He announced before leaving that he would return. This was the first visit paid by the Turkish Ambassador for over a fortnight. He did not see Sir Edward Grey, but had a long conference with Sir Arthur Nicolson, Permanent Under-Secretary."

Edinburgh Evening News.

The only possible answer to this extraordinary conduct was a declaration of war.