America's Highways 1776–1976: A History of the Federal-Aid Program/Part 1/Chapter 5

Good

Roads

Movement

Rural Roads in the Late 19th Century

Railroad competition drove the long-distance wagon freighter and stagecoach companies out of business in the 1850’s and 1860’s, and traffic fell off to the point where toll road operation was unprofitable. Some of the turnpike companies were able to sell their roads to the counties for much less than they cost originally; but most of them simply surrendered their charters and ceased operation. Their facilities were then taken over by the local authorities and maintained as common roads. With the heavy through traffic gone, the more prosperous counties were able to maintain these roads in fairly good condition for local travel.[N 1] In the poorer counties, travel became more and more uncomfortable as the old turnpikes deteriorated from lack of care.

In the East, the old turnpikes were only a fraction of the mileage under county and township control. Most of the people lived along roads that were established in the early days of settlement through continued public use rather than by plan. These followed the boundaries between farms or occupied the lands least suited for agriculture, and, thus, were often winding and poorly located. Over the years, they had been improved by the county and township supervisors with what scanty funds they could raise from taxes, and practically everywhere, except in the wealthiest counties, these roads were maintained by statute labor.

A 1948 map of Kansas showing State highways generally located on a grid pattern, a carry over from the days when roads were built on section lines and each owner donated land for the right-of-way.

The local road situation was somewhat different in the “public land States”—i.e., those States that had been formed from the public domain.[N 1] The lands in these States had been subdivided into rectangular townships and sections according to an ordinance of May 29, 1785. These land lines became the boundaries between farms and, thus, were the lines of least resistance for local roads. The customary right-of-way for these roads was one chain wide, or 66 feet, each property owner donating 33 feet on his side of the section line. As in the East, these roads were normally maintained by statute labor.

In the Great Plains and the Far West, this tendency to fix the local roads on the section lines was strengthened in July 1866 by an act in which Congress granted a free right-of-way for public roads over unreserved public lands. A number of counties took advantage of this act by declaring all section lines in the county to be public roads, thus, reserving the right-of-way before the lands became private property. The Legislature of Dakota Territory passed an act making all section lines public roads 66 feet wide, to the extent that it was physically possible to build roads on these lines.[2]

Section line roads were easy to build in level country, but in hilly country it was impossible to stay on the section lines and preserve a reasonable gradient.[N 2] The rectangular pattern imposed considerable indirect traffic on those whose destination was diagonal to the land grid. Nevertheless, hundreds of thousands of miles of these section line roads were built as the public land States were settled. Initially, these roads were mere wagon tracks, but over the years many of them were graded and ditched, and some were graveled. This work was aided tremendously by the introduction of blade graders after 1878. Some of these were pulled by 6 horses and in easy country, a mile of ditched earth road could be built in a single day.

The years between 1850 and 1900 have been called the “dark age of the rural road,” yet in this period well over 1½ million miles of rural roads were built in the United States. It is true that, with insignificant exceptions, these roads were unimproved, or at best only ditched and graded, yet in the aggregate they represented a mighty public effort, particularly in the West where population was sparse and the people poor.

The Financing of Rural Roads

Until the early 1900’s, the main sources of local road funds were taxes on property, poll taxes and statute labor. In 1904 only 25 States had laws permitting counties, townships or road districts to issue bonds for road improvement, and in these the privilege was used sparingly and usually only to finance a particularly expensive purchase, such as a steel or concrete bridge. The total expenditures on rural roads from bond issues were only about $3.5 million in 1904.[4]

Property taxes levied for road support varied widely from State to State and from county to county within the same State. As the Office of Public Roads (OPR) observed in 1904,

Unquestionably the bitterest controversies in counties and townships in connection with the subject of road improvement are over proposed increases in the rates of property taxation for road purposes. It is common in many parts of the United States for uninformed though honestly-disposed citizens, to make a determined opposition to a very moderate and perfectly reasonable increase in the tax rate.[5]

The average tax rate of all counties reporting to the OPR in 1904 was 25.7 cents per $100 valuation, but this gives little idea of the tremendous variation between counties, some of which levied only 1.3 cents per $100 valuation and some as much as $1.60 per $100 valuation.[6] These taxes, together with poll taxes payable in cash, were by far the major source of funds for building and maintaining the country roads, yielding some $53.8 million in 1904. While this seems like a large sum, it amounted to very little when spread over 2.1 million miles of road.[7]

In 1904 11 States assessed an annual poll tax varying from $1 to $5 per person for upkeep of the roads. This tax could be paid in labor or in cash. In addition, 25 States retained the ancient statute labor system under which all able bodied male citizens of certain ages living along a road were required to work on its repair a stated number of days per year or pay the equivalent in cash.[N 3] Despite its inefficiency, the work rendered in 1904 by statute labor was valued by the OPR at $19.8 million, and amounted to about one-quarter of all rural road expenditures that year.[9]

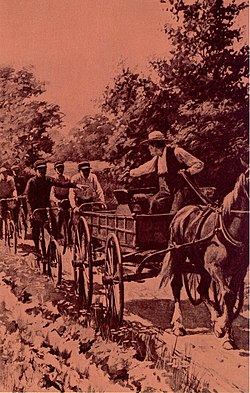

Working out the road tax on a gravel road. Ten days labor or $5 tax was required by law in Alabama as late as 1913.

Most of the rights-of-way for county and township roads were donated by their owners to the local authorities, and these donations represented a very considerable part of the original cost of these roads. Over the years, these rights-of-way came to some 10.4 million acres of land, valued in 1904 at about $342 million.[10] The roads themselves probably represented an investment of at least a billion dollars.

- ↑ All States except the Original Thirteen, and Maine, Vermont, Kentucky, Tennessee, West Virginia and Texas.

- ↑ In 1900 there were more roads having excessively steep grades in Iowa than in Switzerland.[3]

- ↑ As late as 1889 no cash poll taxes or property taxes were levied for road purposes in Kentucky, South Carolina, Georgia, Alabama, Mississippi, Louisiana, New Mexico and Utah, and the rural roads in these States were built and maintained exclusively by statute labor.[8]

This large investment was, however, spread so thinly that very few rural residents enjoyed adequate road service. In the northern States, earth roads were quagmires during the spring thaw and became distressingly soft during rains at any time of year. Deep sand was a problem in many parts of the South. Either way—loose sand or deep mud—the loads a farmer could haul with his teams were only a fraction of what they would have been on a reasonably good road, and this difference was, in effect, a tax on everything the farmer bought or sold. The following account of one farmer’s struggle with his local roads is typical of the era:

After the war I lived 9 miles north of Charlotte. The roads at times were so very bad that everybody was landlocked; the ladies could not go to church in winter; they hardly ever thought of going to town. The men went on horseback and sometimes it took a good thoroughbred to carry you there. . . . The first thing that impressed me with the importance of good roads occurred in 1867. It rained almost everyday for a month; the roads were horrible. I left home with two wagons, one with four horses and one with three, to go to Charlotte, only 9 miles away, for some fertilizer. I got a ton on one wagon and half a ton on the other, and when within a mile and a half of home on the return trip we stalled, and had to take the horses out and leave the wagons there all night. We went back after the wagons the next day and it took until nearly 11 o’clock to get them home. The merchant from whom I got the guano paid $5 per ton freight on it from Baltimore to Charlotte. Considering everything, it cost me over twice as much to take the guano 9 miles from Charlotte to my home as it did to bring it from Baltimore to Charlotte on the railroad.[11]

The Jefferson Memorial Road near Charlottsville, Va. before improvement.

The mud could be so sticky that a pair of oxen had difficulty getting these wheels, without a load, free.

- Jump down and hold the animal’s head, to prevent his dashing it about to his own injury.

- Loosen the check-rein (if you are so foolish as to use one) and the parts of the harness which fasten on the vehicle

- Back the carriage so as to get the shafts and traces clear.

- Steady and support the horse’s head, and excite and encourage him, with hand and voice, to rise.

- When you have got him up pat and further encourage him, and see if he is wounded or otherwise injured.

- Let him stand still a short time and recover himself, and then proceed gently and with greater caution than before.

The high cost of transport from the farms was also a tax on the people of the cities who were forced to pay higher prices for locally grown food and farm products. In 1901 fruit from California could be shipped to Raleigh, North Carolina, by rail for less than farmers living only 15 miles away could deliver their fruit to the Raleigh markets.

You see by this that the railroads enable the fruit growers of California to compete with the fruit growers of your own county towns. . . . The way to successfully compete with these people is to build good roads so as to enable us to get to market at any time and carry a full load, thereby reducing cost of transportation. . . . A bad road is a relentless tax assessor and a sure collector.[12]

Transportation in the Cities

According to the 1900 census, there were 161 cities of more than 25,000 inhabitants. Of these, 27 had populations in the 100,000 to 300,000 range and 11 had more than 300,000 people.

The ability to move goods freely from place to place was absolutely necessary to the prosperity of these cities. Industry, powered by steam, used great quantities of coal which had to be hauled over the streets from the docks and railroad yards to the factories and mills. Similarly, the hauling of raw materials and finished goods to and from the factories, warehouses, docks and railroads generated a tremendous volume of truck and dray traffic. Outside of the industrial areas, city dwellers depended on their streets for deliveries of coal, ice and groceries.

A typical 3-horse truck of the 1890’s weighed 7,000 pounds empty and could carry a 10-ton pay load, and horsedrawn trucks and drays capable of hauling 18-ton net loads were fairly common in large cities. These vehicles ran on steel tires which pulverized all but the hardest pavement surfaces. Consequently, the main streets of the large cities were built very heavily and surfaced with granite blocks or hard paving bricks.[N 1] The minor business streets and residential streets were commonly of macadam or gravel, and in the 1890’s many of these were made dust-free by asphalt surfacing.[14][N 2]

For the most part, city dwellers enjoyed excellent local transportation. Even comparatively small cities had horsecar lines, some of which persisted into the early 1900’s. About 1873 cable railways were introduced in the larger cities, but in the 1890’s these, as well as most of the horsecar lines, were converted to electric propulsion. “By 1890 more than one hundred American cities had installed or were in the process of installing electric street railways.”[16]

Small towns on the peripheries of the large cities were tied to the cities by steam railroads and after about 1894, by electric interurban railroads as well. Frequent schedules on these railroads made it convenient for thousands of the more prosperous city workers to live in the suburbs and commute to work.

- ↑ Broadway in New York City was surfaced with blocks of granite 10 inches thick laid on a 6-inch concrete base; and in Philadelphia pavements for important streets were made of 8-inch stone cubes laid on beds of gravel 15 inches deep.[13] In the 1890’s these stone pavements were overlaid with asphalt to reduce noise and rolling resistance and to provide better footing for the horses.

- ↑ Asphalt paving was first used in New York and Philadelphia in 1871 and immediately became popular because of its smoothness, silence and ease of cleaning. By 1897 over 27.4 million square yards of asphalt were laid in American cities.[15]

The Financing of Urban Roads and Streets

The Cherrelyn Horsecar was unique among horsecars of the day for the horse only pulled the car one way and was a nonpaying passenger on its return trip. It operated up and down the steep hill from downtown Englewood to Cherrelyn (Colorado), a distance of almost a mile, between 1883 and 1910. The horse, sometimes wearing a straw hat, riding on the special platform on the back of the car was a popular attraction for both tourists and residents. Today the old Cherrelyn is restored and is on display near the City Hall in Englewood.

Even the streets of some towns were nearly as bad as the rural roads after a heavy rain.

Most city street improvements were financed by bond issues which were amortized out of general tax revenues. The cities for the most part avoided “pay-as-you-go” financing and did most of their original construction by contract.

Broken and abandoned carriages were the eyesore of the day.

Practically all American cities enjoyed the right, conferred upon them by the State legislatures, to assess the cost of street improvements to the benefited property. This power greatly enlarged the financial resources available to the cities for improvements.[N 2]

City dwellers were exempt from the obligation to perform statute labor. Instead of relying on the obsolete and wasteful statute labor system, cities accomplished their street maintenance with paid labor under the supervision of civil engineers or, at the least, persons with some knowledge of roadbuilding, and paid for it out of general tax revenues.

Beginning of the Good Roads Movement

The great disparity between the cities and the rural areas in the quality of life was evident to everyone, but few city dwellers thought they had any obligation to do anything about it. They had taxed themselves to build their roads and streets, let the farmers do likewise, was the prevailing sentiment in the cities. Nevertheless, the impetus for road reform came from the cities and primarily from civic leaders who appreciated the economic burdens laid on city dwellers and farmers alike by the bad roads. These leaders realized and accepted the cold hard facts that good roads were impossible without adequate funds and that these could be obtained only by the taxation of urban, as well as rural, property.

In 1879 the General Assembly of North Carolina passed the “Mecklenburg Road Law” permitting that county to levy a road tax on all property in the county, including that in Charlotte, the principal city. The act was repealed the following year, but was re-enacted in 1885, and eventually most of the counties of the State elected to operate their roads under this law. By 1902 Mecklenburg was acknowledged to have the best roads in North Carolina, and its citizens were cheerfully paying the highest road taxes in the State: 35 cents per $100 property valuation, plus $1.05 on the poll.[19]

The first State road convention was held in Iowa City, Iowa, in 1883, primarily to try to bring about some improvement in the deplorable condition of the rural roads. This convention recommended payment of road taxes in cash instead of labor, consolidation of road districts, letting road construction to responsible contractors, and, most importantly, authorizing county boards to levy a property tax to create a road fund. These recommendations were adopted by the Iowa Legislature in an act passed in 1884, but the reforms were made optional with the counties rather than mandatory.[20]

- ↑ In 1907, the first year for which reliable figures are available, there were 47,000 miles of roads and. streets in cities of 30,000 or more population, of which 20,646 were improved with some kind of surface better than dirt. These included 7,675 miles of heavy-duty pavement; 4,161 miles with asphalt surfaces; 6,274 miles of macadam; and 2,536 miles of gravel.[17]

- ↑ The special assessment is an institution of American origin, first used in New York City in colonial times to finance streets and sewers. By 1893 all States and Territories had laws authorizing municipal corporations to assess the cost of physical improvements against benefited properties. Street railway companies were customarily assessed with the cost of paving between their tracks, and for a certain distance on each side. The right to make special assessments was rarely conferred on counties and townships, but in some States special road improvement districts were created by the legislature and given the power of assessment.[18]

Other States adopted “good road laws” similar to North Carolina’s and Iowa’s, but the good roads movement did not really get underway until about 1890 when the organized bicyclists launched a national public relations campaign to whip up sentiment favorable to more and better roadbuilding.

As a result of the Mecklenburg Road Law, loads such as this could be hauled by two mules on a macadamized road in any weather where formerly only two bales of cotton could be hauled on an earth road in fairly good weather.

The Wheelmen and The Roads

Bicycles became practical vehicles for personal transportation with the introduction of the “safety” design[N 1] in 1884 and the pneumatic tire in 1888. Almost overnight cycling became a national craze in the United States. “A frenzy seized upon the people and men and women of all stations were riding wheels; ardent cyclists were found in every city, village and hamlet.”[21]

The wheelmen were not content to do their riding on the relatively smooth city streets, but fanned out into the country in all directions. They organized cross-country rallies, road races, weekend excursions. These activities brought the wheelmen into intimate contact with the miserable country roads, and they became vociferous advocates of road improvement.

- ↑ They were called “safety” bicycles because, unlike the “ordinary” bicycle with its high front wheel, the rider was less apt to be propelled over the handlebars if he hit an obstacle.

A leisure bicycle trip into the country about the turn of the century.

All over the country, the bicyclists formed social organizations, or “wheel clubs,” to promote cycling as a sport. Leading this movement nationally was the League of American Wheelmen, which had been organized in 1880 by consolidating a number of local “ordinary” bicycle clubs. Very early in its life the League perceived that cycling as a sport depended on good roads, and it transformed itself into a powerful propaganda and pressure group for promoting them. “Newspaper space was freely utilized; many papers making special and regular features of ‘good roads’; pamphlets were published and distributed broadly, and a magazine was established.”[22] Appropriately, this magazine was titled Good Roads, and it was launched in 1892 under the energetic editorship of I. B. Potter, a New York City civil engineer and lawyer. Good Roads circulated far beyond the ranks of the wheelmen and was very influential in molding public opinion to accept the inevitable taxes that would be required to create good roads. Potter heaped ridicule on American roads by contrasting their sad condition with the fine roads of Europe, particularly those of France. He ran testimonials, praising good roads where they existed in the United States. He also published educational articles on the principles of good roadbuilding and the economic benefits of all-weather roads. He used pictures of good and bad roads freely, thus, holding the reader’s attention where words alone would have failed. Newspapers and national magazines reprinted these articles, affording them the widest distribution.[23]

A “Good Roads Association” was formed in Missouri in 1891, followed by similar organizations in other States.[24] A national road conference, the first of its kind, was held in 1894 with representatives from 11 States. Resolutions passed at this conference urged the State legislatures to set up limited systems of State roads, and to create temporary highway commissions to recommend suitable legislation to implement good roads programs.[25]

State Aid Spreads the Financial Burden

In 1890 all the public roads in New Jersey outside of the cities were under township control and were built and maintained at township expense. Purely local traffic predominated on most of these roads, but some carried traffic from neighboring townships and even beyond, and on a few, teams could be counted from as many as 20 townships. By actual count, the New Jersey Road Improvement Association proved that the traffic on these main roads was intercounty rather than local, and it asserted that, in fairness, the counties and the State should shoulder part of the burden of building and maintaining them. The Association and the League of American Wheelmen put their support behind a State-aid bill in the Legislature which became law April 14, 1891. This law declared that “The expense of constructing permanently improved roads may reasonably be imposed, in due proportions, upon the State and upon the counties in which they are located.” It left the initiation, planning and supervision of State-aided projects in the hands of the county officials, but reserved to the State, represented by the Board of Agriculture, the right to approve projects and to accept or reject contracts. Upon completion, the cost of the improvement was to be split three ways: one-tenth to be assessed to the property holders along the road, one-third to the State and the remainder to the county. The act appropriated $75,000 as the State’s share for the first year’s operations.[26]

The State-aid act was challenged in the courts and upheld. The Board then approved petitions for State aid to three projects in Middlesex County totaling 10.55 miles which, when completed in December 1892, became the first roads to be improved under the act.[27]

In 1894 the operation of the act was placed under a Commissioner of Public Roads appointed by the Governor for a 3-year term. New Jersey, thus, became the second State, after Massachusetts, to establish a State highway organization. For a number of years, however, the Commissioner of Public Roads had very little real authority over State-aided roads and none at all over other roads. Lacking the power to initiate projects, he could not insure that State-aided roads would link up into highways of any great continuous length, and after they were completed, he could not require that they be adequately maintained.

“The Right-of-Way”—bicyclists and horsecart vying for the road.

Nevertheless, the New Jersey State-Aid Act was a milestone in the history of highway administration in the United States, for it clearly stated the principle that highway improvement for the general good was an obligation of the State and county, as well as the people living along the highway. The act also imposed much-needed reforms in local road administration: it abolished the numerous road districts, along with the overseer method of road improvement, and required the township committees to adopt a systematic plan for improving the highways.

The First State Highway Department

Massachusetts approach State aid somewhat differently from New Jersey. The Legislature created a 3-man continuing commission and charged it with the building and control of a system of main highways connecting the municipalities of the Commonwealth. Originally, the counties were supposed to grade these roads, after which the Highway Commission would surface them. In 1894, the law was changed to require the Commission to shoulder the entire cost of construction, charging one-quarter of the expense back to the counties.[28] At the same time, the Legislature appropriated $300,000 to begin the operation of the Commonwealth Highway Plan, an amount that was afterward substantially increased from year to year. The Massachusetts plan was a tremendous improvement over the New Jersey State-aid law. First, it concentrated the limited State funds on a small mileage of the most important roads, thus, assuring that they could eventually be connected into a continuous network. The power to initiate projects remained with the local officials, but the Highway Commission had authority to approve or reject and also to make the surveys and plans and to award and inspect the construction contracts, thus, retaining control over standards. This control eventually led to establishing statewide standards for highways of various classes and also to setting standards for materials used in roads. Finally, the Massachusetts plan left the maintenance of the roads improved with State aid under the direct control of the Highway Commission, which could charge a part of the cost back to the local governments.[29]

The State-aid principle, in various forms, spread slowly to other States after New Jersey and Massachusetts had shown the way. In some States the aid consisted only of advice, which might be accepted or rejected by the local authorities ; but in New York the State Highway Commission was given direct or indirect supervision over every public highway in the State. Four States helped only to the extent of putting convicts from the State penitentiary to work on the roads, while others authorized the employment of State and county convicts for road work and gave cash grants in addition. Illinois conducted a large stone-crushing operation with convicts and gave the stone to the counties free, except for the cost of hauling. Maryland, New Hampshire, New York, Washington and California required all State aid to be spent on trunkline road systems.[30] The last States to enact some form of State aid were South Carolina, Texas and Indiana, all in 1917.

Revival of the Federal Government’s Interest in Roads

As the Good Roads Movement gained momentum, its supporters began to put pressure on Congress to provide some kind of Federal assistance to highways. The proposed Chicago World’s Fair, planned for 1893, seemed an auspicious occasion for a demonstration of Federal interest.

In July 1892, a Senate bill was introduced to create a National Highway Commission “for the purpose of general inquiry into the condition of highways in the United States, and means for their improvement, and especially the best method of securing a proper exhibit at the World’s Columbian Exposition of approved appliances for road making, and of providing for public instruction in the art during the Exposition.”[31] Although introduced by Senator Charles F. Manderson of Nebraska, this bill was written by General Roy Stone, a prominent New York civil engineer and good roads booster.[32]

The Senate passed the National Highway Commission bill, but it was lost by adjournment of Congress and failed to become law. However, in the next session, Representatives Allan C. Durburow of Illinois[N 1] and Clarke Lewis of Mississippi introduced resolutions instructing the House Committee on Agriculture to incorporate a clause in the pending agricultural appropriation bill to authorize the Secretary of Agriculture to “make inquiry regarding public roads,” and to “make investigations for a better system of roads.”

The Agricultural Appropriation Act of 1893, as finally approved on March 3, appropriated $10,000 to enable the Secretary “to make inquiries in regard to the systems of road management throughout the United States . . . to make investigations in regard to the best method of road-making . . . and to enable him to assist the agricultural college and experiment stations in disseminating information on this subject. . . .”

The U.S. Office of Road Inquiry

Secretary J. Sterling Morton implemented this statute on October 3, 1893, by setting up the Office of Road Inquiry (ORI) within the Department of Agriculture. To head this office he appointed General Roy Stone as Special Agent and Engineer for Road Inquiry, but was careful to limit Stone’s authority to investigating and disseminating information. He was specifically forbidden to seek to influence or control road policy in the States or counties or to promote or encourage schemes to furnish work to the unemployed or to convicts. “The Department is to furnish information, not to direct and formulate any system of organization, however efficient or desirable it may be.”[33]

With characteristic energy, Stone, whose entire staff consisted of himself and one clerk, sent letters of inquiry to the governors of the States and Territories, and their secretaries of state, the members of Congress, the State geologists and all the railroad presidents, soliciting information on highway laws, the locations of materials suitable for roadbuilding, and rail rates for hauling such materials. By the end of June 1894, the Office of Road Inquiry had issued nine bulletins on these subjects, some of which were already in their second printing![34]

In the following year the ORI produced nine more bulletins, three of which were the proceedings of national good roads conventions. The promoters of these meetings had no trouble getting able and influential men on their programs as speakers, including General Stone, and publication of their speeches at Government expense was an easy and cheap way to spread the gospel of good roads throughout the country.

Another major ORI project begun in 1894 was a large-scale Good Roads National Map of all the macadamized and gravel roads in the United States. For this, Stone sent a map of each county to the clerk or surveyor of that county, asking that it be returned with the existing roads laid down upon it. By June 1895, he was able to compile statewide road maps for Pennsylvania, Indiana and New Jersey from these county maps, with those of other States in various stages of compilation.[35]

- ↑ Mr. Durburow was Chairman of the Select Committee on the Columbian Exposition.

To round out a year of extraordinary activity, the ORI, with the help of the Division of Statistics of the Agriculture Department, compiled information on the cost of hauling farm products to market in 1,160 counties in the United States. These statistics showed that a farmer’s average haul to market or shipping points ranged from 6.4 miles in the East to 23.3 miles in the Far West, with a national average of 12.1 miles. The average load for a 2-horse team was a little over 2,000 pounds and the average cost of hauling was 25 cents per ton-mile.[36] By comparison, the cost of hauling farm products by railroad was about ½ cent per ton-mile at this time.

The Object Lesson Road Program

As yet, General Stone had not found a satisfactory way to assist the agricultural colleges and experiment stations to disseminate information on roadmaking. A solution to this problem came out of the experience of the State Highway Commission in implementing the Massachusetts State-aid law of 1893. The Legislature had appropriated $300,000 with the provision that each county was to receive a “fair apportionment.” The Commission decided to parcel the money out to 37 widely scattered projects, each about 1 mile long, on the theory that once the people had a taste of good roads, they would put pressure on the Legislature for a bigger future appropriation. Each project was located where it would eventually form a link in a continuous system of trunk roads between the principal cities.[37]

Stone proposed to apply the Massachusetts idea nationally by building short “object lesson roads” near or on the experimental farms of the various States. These would serve to instruct the roadmakers, to educate the visiting public and to improve the economic administration of the farms.[38] This plan was satisfactory to James Wilson, the new Secretary of Agriculture, who preferred that the ORI emphasize the practical side of roadbuilding rather than the academic. However, the total annual budget of the Office of Road Inquiry was only $10,000 at this time, so General Stone had to scrounge most of the cost of the first object lesson roads.

He began the scrounging by reducing his own office staff, using the money saved to hire practical roadbuilding experts, of whom the first was General E. G. Harrison of Asbury Park, New Jersey, a civil engineer who enjoyed a national reputation as a builder of macadam roads. Next, he talked the road equipment manufacturers into providing equipment free as a good will and promotion gesture. Finally, he got the experiment stations, the local road authorities and, in some cases, private individuals to put up the cash to pay for labor, materials, hauling and part of the wages of the machine operators.

The ORI’s share of the cost of each project consisted only of the salary and travel expenses of the supervisory road expert, the expense of transporting the loaned equipment to and from the project and part of the wages of the equipment operators. However, the design, stakeout and supervision of construction were under the complete control of the ORI supervisor, “in order that the roads may be creditable to the Government when done.”[39]

Building the first object lesson road near the New Jersey Agricultural College and Experiment Station, New Brunswick, N.J., in 1897.

The first object lesson road project was comparatively small, involving a cash outlay of only $321 put up by the New Jersey Agricultural College and Experiment Station at New Brunswick. Under this project, General Harrison, in June 1897, placed 6 inches of trap rock macadam 8 feet wide on a 660-foot section of the main road leading from the town to the college farm. He then moved the equipment to Geneva, New York, where he built 1½ miles of road connecting the city to the New York Agricultural Experiment Station. This road cost $9,046 and was financed by contributions from the town of Geneva, the experiment station and three private individuals. After its completion, Harrison moved the equipment to Kingston, Rhode Island, where he completed a road for the Agricultural College of Rhode Island in 1898.[40]

Working the road machine on a section of the experimental road at Geneva, N.Y.

These roads accomplished their intended purpose. They were a forceful demonstration of General Stone’s “seeing is believing” philosophy of selling good roads to the public. They attracted hundreds of visitors, including many county road officials. They also attracted a deluge of requests for similar object lesson roads at other agricultural colleges which Stone was unable to fill because his funds had run out. In September 1897 he wrote:

The work now in hand will exhaust all the funds that can be spared from this year’s appropriation, unless something additional is provided to meet the many urgent demands of the agricultural colleges and experiment stations for ‘Government’ roads.

If the manufacturers continue willing to furnish the machinery free, an expenditure by the Government of from $300 to $500 for each locality will be sufficient to call out enough local help to build from $2,000 to $10,000 worth of road at most of the 116 agricultural colleges and experiment stations, and any required number of outfits can be put in the field at once. . .[41]

Educational Work of the Office of Road Inquiry

General Stone and his deputy engineer, Maurice O. Eldridge, were indefatigable writers and speakers. In addition to writing or editing 20 published bulletins and 30 circulars on various aspects of the road problem, they accepted invitations to appear on the programs of several dozen good roads conventions and farmer’s road institutes. The invitations were, in fact, far more numerous than the ORI could accept with its limited budget and force. General Stone was also an acknowledged expert on good roads legislation, and his advice was sought by several States, notably California, New York, Connecticut and Rhode Island, in framing their highway laws.

Following the outbreak of war with Spain, General Stone, in August 1898, was granted leave of absence from the ORI to serve with the Army. During the war he was a Brigadier General on the staff of General Nelson Miles. The war over, he resumed his duties in January 1899, but resigned October 13, 1899, to return to New York, where he accepted the presidency of the National League for Good Roads, an organization he had helped to found in 1893 before his appointment to the Office of Road Inquiry.

The Office of Public Road Inquiries

While General Stone was on military duty, the Office of Road Inquiry was temporarily headed by Martin Dodge of Cleveland, Ohio, formerly President of the Ohio State Highway Commission. When Stone resigned in October 1899, the name of the agency was changed to the Office of Public Road Inquiries (OPRI) and Mr. Dodge was appointed as Director.

General Stone’s plan for three great demonstration roads—from Portland, Maine, to Jacksonville, Fla., on the east coast; from Seattle, Wash., to San Diego, Calif., on the west coast; and from Washington, D.C., to San Francisco, Calif.

About 1898 Martin Dodge advanced the idea of steel track wagon roads by exhibiting sections of steel track at the Trans-Mississippi Exposition at Omaha. The advantages were that steel track was less costly to install and maintain, more durable, and the power required to move a vehicle was only a small fraction of that needed over any other kind of road. This demonstration shows an 11-ton load being hauled by one horse on a steel track while it would take 20 horses to haul this load on an ordinary road of that day.

For 2 years, prior to General Stone’s resignation, Congress had turned a deaf ear to his entreaties for more funds to expand the demonstration road program. When Mr. Dodge took office in 1899, the budget was still only $10,000 per year, and for another 2 years he had no success in getting it increased. This resistance was due, in part at least, to fear on the part of some people that the OPRI was the entering wedge for national roads under Federal control. Seeking to allay this suspicion, Dodge wrote in his report for 1901:

It is proper just here to call attention to a misconception which appears to exist in the minds of some to the effect that increased appropriations for this work may lead to National aid. It should be distinctly understood that the work of this Office, like that of many other Divisions of the Department, is purely educational. In requesting an increased appropriation it was not the intention to shift the burden and responsibility of constructing improved roads from the States and counties to the General Government. Such a plan is not feasible, and even if it were, it would not be desirable, for there could be no surer way of postponing the building of good roads than by making them dependent upon National aid. Under such a system States and counties would wait for National aid and little or nothing would be done.[42]

Director Dodge’s plea for more funds did not bear fruit until 1903 when Congress increased the OPRI’s budget to $30,000. In the meantime, to better keep in touch with local developments and economize on travel expense, Dodge divided the country into four “divisions,” with a special agent in charge of each. To head the Eastern Division, he appointed Logan W. Page, a geologist who at the time was also Chief of the Bureau of Chemistry’s Division of Tests. Page had been invited to Washington in 1900 to set up a materials laboratory in the Bureau of Chemistry of the Department of Agriculture and to conduct a study of road materials on a national scale. The other division heads were Professor J. A. Holmes of Chapel Hill, North Carolina, J. A. Stout of Menominee, Wisconsin, and James W. Abbott of Denver, Colorado.

All of the division agents, except Page, were parttime employees, and their available time was fully employed attending conventions, writing articles and collecting information on the progress of legislation. An idea of the duties of these agents can be gleaned from Dodge’s summary of Special Agent Abbott’s work for 1901. In addition to traveling more than 12,000 miles by railroad,

He attended and participated in the work of four very important conventions, at two of which he read papers. He has written several articles for publication in leading newspapers, and numerous interviews have been published giving accounts of his movements and work. He spent some time in consultation with the road committees of the Colorado legislature and assisted in framing a carefully prepared road law. He visited many places in Colorado, Utah, and California, and gave advice where it was desired regarding specific or general road improvement. Mr. Abbott visited, practically at his own expense, this Office and the highway departments of New York, Massachusetts, and California. . . .

. . . He has, by personal interviews and private letters, brought the subject of road improvement to the attention of governors and other State officials, the editors of leading newspapers, professors in institutions of learning, presidents and managers of railroads, prominent civil and mining engineers, members of the legislatures, boards of county commissioners, road supervisors, the heads of leading industries, manufacturers of road machinery, besides a large number of influential private citizens.[43]

All this for $1,500 per year! Obviously, Special Agent Abbott also had a private income to draw upon, as did the other division heads.

Until 1903 the OPRI had only one object lesson road construction team, which was managed by Special Agent and Road Expert E. G. Harrison until his death in February 1901. This team was shipped from place to place by rail on a prearranged schedule, building eight or nine roads per year, each ½ to 1½ miles long. After a sufficient amount of road had been built at each location, a “good roads day” would be arranged, and the farmers of that and the adjacent counties would be invited to attend. Special Agent Harrison would lead the crowd—often as many as 500 persons—along the new construction, lecturing on the fundamentals of drainage, stone surfacing and road maintenance. Harrison would arrange for the lecture to be printed in the local newspaper. The following is a brief quote from one of these accounts:

‘We are not here to build city streets, nor boulevards. Cities are able to pay for their expensive streets and know how to build them. But the U.S. is interested in the rural districts and wishes to help the farmers and others to get good roads. Therefore, the Department of Agriculture has established the Office of Road Inquiry, which is seeking to gather all the information possible about the construction and maintenance of good roads and to impart it gratis to the people. The government will not build your roads, but will place at your disposal all the information it has gained from experts, experiments and other sources. . . .

‘Here we have not even built the best kind of macadam road. For that you must go to your cities and look at the boulevards. We have simply taken the material at hand and from it constructed the best road possible with the money we have. The boulders from which the stone is crushed were brought from the neighboring farms. They are of good quality and very hard. They consist of granite, trap, syenite, quartz, etc. This is much better than your soft limestone, or loose sandy, washed gravel.’[44]

After 1903, with a tripled budget, the OPEI was able to keep four demonstration teams in the field. Also, with Page’s new laboratory in operation, the Government undertook to test the materials going into the object lesson roads without charge to the local cooperators, eliminating guesswork in this very important aspect of roadbuilding.

The Good Roads Trains

In 1893 there was only one national good roads organization in the United States and three or four local associations. Eight years later there were over 100 organizations promoting good roads, including six distinctly national road associations. In 1901 the most active and aggressive of these organizations was the National Good Eoads Association (NGEA) which had been formed during the Chicago Good Roads Convention of 1900, and was headed by Colonel William H. Moore of St. Louis as president and Colonel R. W. Richardson of Omaha as secretary. Like many other good roads organizations, the National Good Roads Association had no permanent membership list and depended for its support on donations from civic groups, manufacturers of road machinery, suppliers of road materials, wealthy individuals, the public at large and even the railroads.

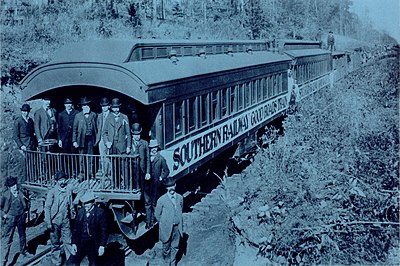

The Southern Railway Good Roads Train with some of the road experts during its fall trip in 1901.

Colonel Moore, the guiding spirit of the NGRA, was a skillful and persuasive promoter, with a wide acquaintanceship among influential people. In 1901 he conceived the idea of a traveling good roads show that would cover the country, educating the public on the advantages of improved highways, very much in the manner of the circuses and the popular Chautauqua shows. He persuaded the road machinery companies to help with this project by donating their latest models, along with trained operators, to run them. From the Illinois Central Railroad, he obtained the promise of an 11-car train free of charge, to transport the show from place to place. Finally, he approached Director Dodge to give Government sanction to the idea by providing a road expert to lecture on roads and supervise demonstrations of roadbuilding. Dodge was unable to help because his budget was already committed to other work; however, when the Association offered to pay the expert’s salary and expenses, he agreed to participate and designated Special Agent Charles T. Harrison of New Jersey as the OPRI’s representative.[N 1]

The Association mounted a high-powered publicity campaign to prepare the way for the “Good Roads Train.” Advance agents organized local conventions and lined up donations of labor and materials for demonstration projects. The train, consisting of nine flat cars loaded with road machinery, and two sleeping cars for the operators, laborers, officials, road experts and press representatives, pulled out of Chicago early in April 1901, under the management and control of Colonel Richardson. Before returning in August, it stopped at 16 cities in five States, where the construction crew built sample roads of earth, stone or gravel varying in length from ½ mile to 1½ miles. Director Dodge, who went along on the first trip from Chicago to New Orleans, expressed his enthusiasm for the project in this glowing account:

About 20 miles of earth, stone, and gravel roads were built and 15 large and enthusiastic conventions were held. The numbers attending these conventions and witnessing the work were very large, in nearly every instance more than a thousand persons and in some cases 2,000 persons being present. Among the attendants were leading citizens and officials, including governors, mayors, Congressmen, members of legislatures, judges of the county court, and road officials. This was undoubtedly the most successful campaign ever waged for good roads, and the expedition has been of great service to the cause, and especially to the people of the Mississippi Valley.[45]

At this time the steam railroads were among the strongest supporters of good roads. Secure in their position as the backbone of the American transportation system, they were anxious to extend their tributary traffic areas and also to overcome some of the widespread hostility engendered by their high-handed methods of dealing with the public. The economic aspect of the railway interest in roads was aptly expressed by an official of the Southern Railroad in 1902:

. . . They [the Southern Railroad] now handle the products of from 2 to 5 miles on each side of their tracks. In the winter season they can not get the products that are any farther away. If you had improved roads, they would be able to serve the country 20 to 30 miles from their tracks. . . . If you are a shipper, you know that at some seasons of the year it is hard to get cars; that every railroad in the United States suffers from a lack of cars and locomotives, and that the industries of almost every community suffer on this account. This is because the traffic on all railroads is so greatly congested within a few months of the year. It is not divided over the twelve months as it ought to be. If there were good roads leading to every railroad station in the United States, the railroads would be able to get along with half the cars they now need. . . .[46]

The Illinois Central Railroad “expedition” was so successful that Colonel Moore had little difficulty lining up others. One left Chicago on the Lake Shore and Michigan Southern Railroad for Buffalo, where it was placed on exhibit on the grounds of the Pan-American Exposition during the International Good Roads Congress during September 1901.[47]

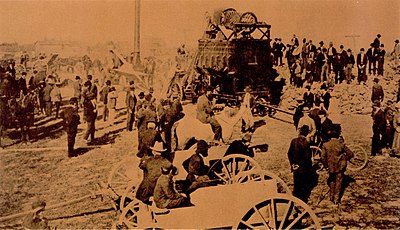

The crushing plant in operation at Winston-Salem, N.C., during a macadam roadbuilding demonstration in 1901.

- ↑ Charles T. Harrison replaced E. G. Harrison who died February 6, 1901.

An itinerant college on wheels has come among us. It brings its professors and its equipment with it. It is known as the ‘good roads train’ of the Southern Railway system. This college does not teach out of books, nor solely by word of mouth. It teaches by the greater power of example. If you will just watch its operation you will see a new good road grow over an old and bad road at the magic touch of titanic machinery, and while an orator talks of road building it will set his words to the music of practical accomplishment.[48]

A steam roller in operation on a demonstration macadam pavement near Greenville, Tenn., in 1901.

The Pere Marquette Railroad and the Michigan Good Roads Association sponsored a Good Roads Train for the summer of 1902—the only train which did not have at least one of Dodge’s road experts aboard. The last of the Good Roads Trains left St. Paul on the Great Northern Railroad, September 8, 1903, for an expedition through Minnesota, the Dakotas, Montana, and beyond to the Pacific Coast.

The First National Road Inventory

One of the most ambitious tasks undertaken by the OPRI during Director Dodge’s administration was an inventory of all the roads in the United States outside of the cities. The information for this enumeration was obtained in 1904 from questionnaires sent to the county authorities or from “voluntary correspondents” appointed by the OPRI. The investigators, headed by Assistant Director M. O. Eldridge, went far beyond merely tabulating road mileage. They investigated taxation and sources of revenue, road laws and total expenditures in every county of every State. Road mileage was subdivided according to surface type. The information was so voluminous that over 2 years were required to tabulate it and issue the report, which did not appear until May 1907.[49]

The OPRI study showed that there were 2,151,570 miles of rural public roads in the United States in 1904, plus 1,598 miles of stone-surfaced toll roads.[N 1] Of the public roads, only 153,662 miles had any kind of surfacing.[N 2] The expenditures on roads in 1904 were $79.77 million of which only $2.6 million was contributed by the States in the form of State aid.[52]

- ↑ By comparison, there were 213,904 miles of railroads in the United States in 1904.[50]

- ↑ This mileage was distributed as follows:

Surfacing Type (Miles) Earth Gravel Stone Shells, etc.

Sand-ClayTotal Eastern and

Southeastern

States580,850 24,627 21,240 3,091 629,808 Texas 119,281 167 1,909 52 121,409 Public Land

States1,297,777 83,439 15,473 3,664 1,400,353 1,997,908 108,233 38,622 6,807 2,151,570 In addition to the above, there were 1,101 miles of stone-surfaced toll roads in Pennsylvania and 497 miles of toll roads in Maryland.[51]

Office of Public Roads Achieves Permanent Status

When the automobile arrived, many miles of rural road were similar to this one along Bishop Creek in California

A plank road between El Centro, Calif., and Yuma, Ariz.

Stuck in the mud in Sacramento Canyon.

Director Dodge recommended that his office be transformed into a Division of the Department “with a statutory roll of officers and employees.”

The work of this Office appears to be no longer of tentative character. Year after year it has assumed increased importance and wider scope, and there is now a general demand coming up from all sections of the country that it be made a permanent feature of the work of this Department. It appears fitting, therefore, that it be given a more definite legal status, thereby adding dignity and stability to this branch of the Department’s work. . . .[53]

Congress eventually heeded this plea, and in the Agriculture Appropriation Act of March 3, 1905 (33 Stat. 882), it merged the Division of Tests of the Bureau of Chemistry with the Office of Public Road Inquiries to form the Office of Public Roads. The new agency had a statutory roll, headed by a Director, “who shall be a scientist and have charge of all scientific and technical work,” at a salary of $2,500 per year. The Act also provided for a Chief of Records, an Instrument Maker and 6 clerks, and boosted the total annual appropriation for the office’s work to $50,000.

The requirement that the Director should be a scientist prevented Martin Dodge, a lawyer, from succeeding to the directorship of the new Office of Public Roads, and Logan Waller Page was appointed instead.

Director Page assumed the helm of the Office of Public Roads at a momentous time in the history of land transportation. To his predecessors “good roads” meant wagon roads, constructed according to the time-tested methods of Trésaguet, Telford and McAdam and designed for horsedrawn steel-tired traffic traveling 6 to 8 miles per hour. In 1905 the shape of things to come was dimly foreshadowed by scarcely 78,000 automobiles, most of which were confined to the cities. Ten years later 2.33 million autos were raising clouds of dust on the country roads, and by 1918 this number had increased to 5.55 million. The motor age had arrived, and with it a new kind of highway, designed specifically for motor vehicles, would evolve. Director Page would preside over the early stages of this evolution. REFERENCES

- ↑ J. Owen, The Controverted Questions in Road Construction, Transactions, Vol. 28 (American Society of Civil Engineers, New York, 1893) p. 111.

- ↑ 43 U.S.C. Section 218 (1964).

- ↑ M. O. Eldridge, Good Roads For Farmers, Farmers’ Bulletin No. 95 (Office of Public Roads, Washington, D.C., 1900) p. 9.

- ↑ M. O. Eldridge, Public Road Mileage, Revenues and Expenditures, In the United States In 1904, Bulletin No. 32 (Office of Public Roads, Washington, D.C., 1907) p. 16.

- ↑ Id., p. 18.

- ↑ Id.

- ↑ Id., p. 16.

- ↑ Id., p. 20.

- ↑ Id., p. 16.

- ↑ Id., p. 14.

- ↑ S. Alexander, History of Good Road Making in Mecklenburg County, Proceedings of the North Carolina Good Roads Convention, Bulletin No. 24 (Bureau of Public Roads, Washington, D.C., 1903) pp. 22, 23.

- ↑ T. Parker, Good Roads and Their Relation to the Farmer, Proceedings of the North Carolina Good Roads Convention, Bulletin No. 24 (Bureau of Public Roads, Washington, D.C., 1903) p. 27.

- ↑ W. Gillespie, A Manual of the Principles and Practice of Road Making (A. S. Barnes and Co., New York, 1871) pp. 221, 227.

- ↑ A. Blanchard & A. Fletcher (eds.), American Highway Engineer’s Handbook, 1st ed. (Wiley, New York, 1919) p. 467.

- ↑ G. Tillson, Asphalt and Asphalt Pavements, Transactions, Vol. 38 (American Society of Civil Engineers, New York, 1897) pp. 224, 234.

- ↑ R. Kirby, S. Withington, A. Darling & F. Kilgour, Engineering in History (McGraw-Hill, New York, 1956) p. 396.

- ↑ Office of Federal Coordinator of U.S. Transportation, Public Aids to Transportation, Public Aids to Motor Vehicle Transportation, Vol. IV (GPO, Washington, D.C., 1940) p. 6.

- ↑ L. Van Ornum, Theory and Practice of Special Assessments, Transactions, Vol. 38 (American Society of Civil Engineers, New York, 1897) pp. 336–361.

- ↑ J. Holmes, Roadbuilding in North Carolina, Proceedings of the North Carolina Good Roads Convention, Bulletin No. 24 (Bureau of Public Roads, Washington, D.C., 1903) pp. 66, 67.

- ↑ H. Trumbower, Roads, Encyclopedia of the Social Sciences, Vol. 13 (MacMillan, New York, 1948) pp. 406, 407.

- ↑ G. Chatburn, Highways and Highway Transportation (Thos. Y. Crowell, New York, 1923) p. 128.

- ↑ Id., pp. 128, 129.

- ↑ Id., p. 129.

- ↑ W. H. Moore, Response to Address of Welcome, Proceedings of the North Carolina Good Roads Convention, Bulletin No. 24 (Bureau of Public Roads, Washington, D.C., 1903) p. 12.

- ↑ H. Trumbower, supra, note 20, p. 407.

- ↑ L. Page, Progress and Present Status of the Good Roads Movement in the United States, Yearbook of The Department of Agriculture, 1910 (GPO, Washington, D.C., 1911) p. 270.

- ↑ A. Rose, Historic American Highways—Public Roads of the Past (American Association of State Highway Officials, Washington, D.C., 1953) pp. 94, 95.

- ↑ G. Chatburn, supra, note 21, pp. 150, 151.

- ↑ M. Eldridge, G. Clark & A. Luedke, State Highway Management, Control and Procedure, Public Roads, Vol. 1, No. 9, Jan. 1919, p. 60.

- ↑ L. Page, supra, note 26, pp. 273, 274.

- ↑ 23 Cong. Rec. 6846 (1892).

- ↑ G. Chatburn, supra, note 21, p. 133.

- ↑ Bureau of Public Roads Annual Report, 1893, Letter From Secretary Morton to General Roy Stone, Oct. 3, 1893, p. 586.

- ↑ Bureau of Public Roads Annual Report, 1894, p. 217.

- ↑ Bureau of Public Roads Annual Report, 1895, p. 198.

- ↑ Id., p. 197.

- ↑ G. Perkins, State Highways in Massachusetts, Yearbook of The Department of Agriculture, 1894 (GPO, Washington, D.C., 1895) pp. 508, 509.

- ↑ BPR, supra, note 35, p. 198.

- ↑ Bureau of Public Roads Annual Report, 1897, p. 174.

- ↑ U.S. Department of Agriculture, Yearbook of The Department of Agriculture, 1897 (GPO, Washington, D.C., 1898) pp. 376–379.

- ↑ BPR, supra, note 39, p. 174.

- ↑ Bureau of Public Roads Annual Report, 1901, p. 251.

- ↑ Id., p. 238.

- ↑ Gen. Harrison Tells How the Road Was Built, The Road Maker, Vol. 1, No. 3, (Port Huron, Mich.) p. 6.

- ↑ BPR, supra, note 42, p. 243.

- ↑ M. A. Hays, Interest of Railways in Road Improvement, Proceedings of the North Carolina Good Roads Convention, Bulletin No. 24 (Bureau of Public Roads, Washington, D.C., 1903) pp. 15, 16.

- ↑ Bureau of Public Roads Annual Report, 1902, p. 309.

- ↑ Bureau of Public Roads Annual Report, 1903, p. 337.

- ↑ M. O. Eldridge, supra, note 4, pp. 5–7.

- ↑ Id., p. 11.

- ↑ Id., pp. 8, 9.

- ↑ Id.

- ↑ BPR, supra, note 48, p. 347.